For audio version, visit kswheat.com.

Deb and Ken Wood share their farming story through tornado recovery to retirement and beyond

The lives of one Kansas farm family was forever changed after a large and violent long-track tornado tore across north central Kansas on May 25, 2015. Ranking as one of the most violent tornadoes of the season with an EF4 rating and estimated winds of 180 miles per hour, the funnel was on the ground for more than a staggering 90 minutes, bending railroad tracks and snapping trees three or four feet wide in half.

The worst damage was to a single farmstead one mile southwest of Chapman, where the home and all the outbuildings were completely blown away as the operation’s matriarch hid in the basement underneath pillows. But what could be only a story of devastation is also one of hope, community and resilience for Ken and Deb Wood, who shared their story with Aaron Harries, Kansas Wheat vice president of research and operations and host of the Wheat’s on Your Mind podcast.

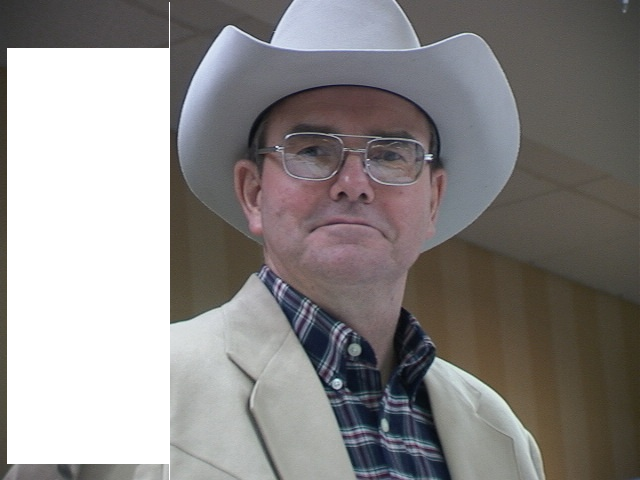

Today, Ken is a retired wheat farmer, who has served on the boards of the Kansas Association of Wheat Growers and the National Association of Wheat Growers. He still serves as a board member for the National Wheat Foundation. Deb works as a family resource management agent for K-State Research and Extension in Salina.

The day the tornado struck wasn’t expected to be a very severe weather day. Ken was away in Hays for KAWG meetings and Deb went to and came home from work like normal. Their farmstead was picturesque, located in a river bottom with a traditional farmhouse, nine outbuildings and all the machinery you would expect on a working farm – minus the combines that were stored at a different location. Ken had all his corn and about half of his soybeans planted and he recalled he was three weeks to a month out from wheat harvest.

Deb came home like any other day, got a bite to eat and had the news on. There was a storm building east of Bennington, but it was Kansas and May, so thunderstorms and tornadoes are just part of the normal weather broadcast.

“There’s tornadoes around Kansas all the time, so I didn’t think too awful much of it until things started getting closer,” Deb said. “Looking back, if I knew then what I know now, I would have put as much stuff into my vehicle as I possibly could have and gotten the heck out of Dodge.”

Ken stayed in Hays for supper. He got an alert on his phone that there was some severe weather developing, but he just watched as it developed like a normal storm. He got on the road and headed for home, but the longer he drove, the more he realized the storm was developing into something dangerous.

In Kansas, tornadoes typically move from the southwest to the northeast or due north. This night’s tornado moved west to east, took a right turn, went south across I-70 and hit the Wood’s farmstead out of the northwest as a monster.

“When you live in Kansas, you spend a lot of time in the basement when there’s a warning,” Deb said. “Most of the time, I go downstairs and I just kind of sit there, listen to the radio and wait for it to be over with. I had done that and then I had gone back up as I was getting texts from people. And that’s when I started worrying.”

Deb quickly gathered what she could – some medicine, work clothes and, importantly, Ken’s work boots. Then she ducked under a desk in the basement, taking pillows off the bed in the room and stuffing them around her. Still, it didn’t occur to her that the storm would take everything else.

Then the storm hit. The glass broke. The subfloor was totally blown away. And the entire house was gone.

“There was nothing left at the farm and I mean nothing left,” Deb said. “There was just nothing. It just chewed everything up into little pieces.”

The glass all broke, it ripped off the subfloor totally. The house’s center beam broke into two and a wall landed on Deb. Then it started raining and then it started hailing. Still, Deb kept her cool.

“I called Ken to let him know we’d taken a direct hit, but I was fine, but I couldn’t get out,” Deb remembered.

A local fireman who had lost part of his own farming operation in a 2008 tornado that hit nearby Chapman was first on the scene. Deb could hear him calling for her, so she started hitting on top of the wall. He removed what he could but had to wait for help to get her out entirely.

Ken got the call when he was in nearby Abilene. He raced down the road but was stopped on his normal route on Old 40 Highway because there were poles across the road. When a deputy came flying around the corner and heading north towards I-70, Ken got behind him and followed him all the way – not stopping at a single stop sign, only slowing when they hit a heavy hailstorm.

By the time Ken got home, it was still light enough to see the damage. Deb had very deep bruises on her back, but no broken bones. Although they had no house, no clothes, no food, the community immediately rallied together. Ken and Deb stayed that night at Ken’s brother’s house, but neither slept a wink.

The next morning brought help that did not stop – from family, friends, neighbors, the community, former co-workers, the KARL program, the wheat family. Anyone and everyone who could offer help did. Two former teachers of Ken offered to rent them a two-story farmhouse west of Junction City that was fully furnished. The couple moved in with half a trash bag full of clothes and a pan of lasagna from a neighbor and lived there for 10 months. Although, the fridge was already so full of offerings that the lasagna barely fit.

In addition to the farmhouse and yard, the couple lost irrigation pivots, bins, other buildings and a couple of pieces of equipment. But one of the hardest chores was cleaning up all the acres where debris was scattered like crumbs.

“It literally just chewed stuff up and so there was a lot of stuff that was spread out over the fields,” Ken said. “Little pieces. You’d find a handle off a truck, and there was a lot of things that you couldn’t tell what they were.”

In addition to picking up individual pieces of debris, Ken and his helpers burned wheat stubble and then had to mine the debris hidden under the stubble. It couldn’t be done all at once, so it was done one smoky, dusty terrace at a time.

Within just a few weeks, it was time for wheat harvest. Luckily, Ken was no stranger to borrowing trucks or tractors from his brother or neighbors. And wheat harvest felt like a return to something normal.

“That was the first thing that felt like I was doing something that’s not picking stuff up and not tornado-related,” Ken said. “Although harvest was a real trip, cutting around stuff out in the wheat fields, that was what got me back into the right frame of mind to at least start a plan.”

The couple navigated insurance and deciding where and how to rebuild their farmstead. The home builders broke ground at the end of September and they moved into their brand-new home the first weekend of the next April.

Their story does not end there. When health issues popped up, Ken made the difficult decision to retire. One of the neighbors who stepped up after the tornado and brought out a loader to help out had a son coming home and wanted to expand his operation. So Ken and Deb made the calls – first to their landlords and then to others – it was time to turn over the operation to a new generation.

“One weekend, that’s about all I did was call people and let them know,” Ken said. “As it turned out, I’ve been way healthier than I was expecting to be from this whole deal, so I could have kept going. But once you make the decision, I’ve been at peace with it pretty much.”

While COVID-19 disrupted retirement travel plans, the Woods have found themselves as busy as ever. Deb now helps share her story about taking an inventory of both everything in the machine shed and in the house, but also putting together a grab-and-go box with all the policy and phone numbers needed if the worst happens. And Ken found he missed serving on wheat industry boards, so he quickly applied when a spot opened up for the board for the National Wheat Foundation.

“Now I’m probably busier than I want to be, but it’s self-inflicted,” Ken said. “So I’m good with that.”

Through it all – farming, tornadoes, rebuilding a home, retiring – Ken and Deb know one truth above all else – it’s the people around you that matter most.

“I feel like we’ve come out on the other side stronger and more resilient,” Deb said. “All of the people that helped us get through the recovery; we couldn’t have done it without them. Building those relationships and keeping in touch with people and having that community – it really helps you get through things like this.”

Listen to Ken and Deb’s full story on the podcast or find other episodes of “Wheat’s On Your Mind” at wheatsonyourmind.com.

###

Written by Julia Debes for Kansas Wheat