Lettuce Eat Local: Cinco De Mayonnaise

Lettuce Eat Local

If Brian and I have a meal that’s “ours,” one that we tend to gravitate towards, it’s fajitas. It kind of covers all the bases: we like to eat it, we like to make it, we like to serve it to guests. It can be cobbled together last minute, or made ahead; just the basics, or all sorts of extras. Everyone gets to make their own, so it works for different taste preferences and allergy restrictions, and is endlessly customizable.

In fact, perhaps its only problem is that when I say “it,” what do I mean? What are fajitas? We could look up dictionary definitions, see restaurant menus, reference culinary sources, check the Spanish etymology, ask some Latino households, poll friends — we could do all these, and still not come to a conclusive decision.

I say “could,” but honestly, Brian and I have done most if not all of those things in our quest for the meaning of fajitas. For a meal so near and dear to our hearts and stomachs, you would think we would have more agreement on what it actually is. There are a lot of “usually”s in reference to fajitas, as in they usually include meat cut in strips, usually involve sauteed peppers, and usually come served with beans.

Except for when they don’t.

There are all the exceptions — as soon as you think you come to a consensus, myriad examples to the contrary appear. In fact, the most constant component is probably tortillas, and then how are they different from burritos or soft tacos? And are fajita bowls an oxymoron then? Because that’s what I usually eat when I make fajitas…so if I’m serving fajitas for supper, and I’m eating supper, how am I not eating fajitas? What if Benson chomps on the tortilla plain and just eats the filling separately, is he actually eating an entirely different meal too?

The questions go on and on. I’m not kidding, I could easily fill the rest of this article with existential questions about fajitas. Considering the lack of accord even after our family’s many discussions on the topic, however, I concede that it may not be the most uplifting endeavor. Brian and I have come to the place where we (and the rest of the culinary world apparently) agree to have disagreements on what exactly makes them themselves; so our house fajitas can contain any arrangement of any assortment of meats, salsas, cheeses, tortillas, beans, veggies, rice…or not. Often I try to avoid titling the meal at all, instead announcing the array with, “Here’s food!”

We at least know fajitas are Mexican, right? Ha, even there there’s no easy answer. They are, because they are eaten in and associated with Mexico, but actually they originate from Texas. But the very recent Cinco de Mayo is Mexican; meaning the fifth of May, this holiday is the annual celebration of Mexico’s victory in 1862 at the Battle of Puebla over the Second French Empire. Those of us who don’t have much cultural heritage with the history of Cinco de Mayo see it as a beautiful excuse to eat Mexican, or at least Mexican-ish, food.

But because I don’t want to start another battle, I obviously can’t give a recipe for fajitas. Quesadillas are from Mexico, and entail far less controversy, so after all that, here you go. ¡Buen provecho!

Cerdo de Mayo Quesadillas

Quesadillas may be Mexican and much easier to define than fajitas (tortillas sandwiched with stuff?), but clearly these are not authentic. I am having too much fun playing with my food and my words; “cerdo” means pork and “Mayo” does mean May, except in this case it means mayonnaise, because that’s what I want. Quesadilla means “little cheesy thing,” so keep your priorities in mind when you’re making these. The mayo might seem odd, but I wanted something creamy but not as robust as sour cream or tangy as yogurt, and I’m going to start doing this more often.

Prep tips: we had extra of this pork all the ways this week: on rice, as tacos (or burritos or fajitas?), tossed in salad. So good.

2 pounds boneless pork butt or shoulder, cut in 1” chunks

1 [15-oz] can pineapple tidbits, packed in juice

¼ red onion

½ green bell pepper and/or deseeded jalapeño

1 teaspoon salt

1 teaspoon cracked black pepper

to assemble: tortillas, mayonnaise, shredded cheese, chopped cilantro

Add pork to a baking dish in a single layer. Top with about half the pineapple chunks, and pour the rest (including the juice!) into a blender. Add the onion, pepper(s), salt, and pepper, and blend until smooth; pour over pork. Bake at 425° for about 40 minutes, until tender. Let meat rest, then shred or chop it, and return to pan juices.

To serve: spread a tortilla with mayonnaise, toss it into a hot greased skillet; top it with a good amount of pork, cheese, and cilantro, and then a second tortilla. Fry until toasted on the bottom, then carefully flip and fry the other side. Remove from heat, and repeat as necessary for all your quesadillas.

Kansas wheat crop deteriorates due to lack of moisture

April showers bring May flowers, but an April without showers brings disappointment to a wheat crop that had a lot of promise coming out of the winter.

According to Ross Janssen, Chief Meteorologist for Storm Team 12 in Wichita, the precipitation in Dodge City last month was 0.02 inches, tying the 1909 record for the driest April on record.

What’s even worse than a continuing multiyear drought is the loss of hope being felt throughout central and southern Kansas for a crop that, in January and February, was one of the better-looking wheat crops they’d seen in the past ten years.

The condition of the crop has been deteriorating rapidly, especially over the past few weeks, going from 57 percent good to excellent on February 25 to only 31 percent good to excellent by April 28, according to USDA’s National Agricultural Statistics Service.

It has suffered from lack of moisture for much of the growing season, especially during the spring green-up. The Kansas wheat crop is also ahead of schedule, with one-third already headed, well ahead of 9 percent last year and 6 percent average. A March 26-27 freeze event took a toll on it, as there was not enough snow cover, and the plants were more advanced than they typically are at the end of March.

Mike Hubbell, a farmer from the Spearville area in Ford County, said his wheat came up good last fall, received a decent snow in February, was pretty wet in late January and February, and was looking pretty good. However, the last decent moisture it received was on February 5. Since then drought has killed off some tillers and it’s going downhill pretty rapidly.

A field of T158, planted on September 28, 2023, showed drought stress and freeze damage. Hubbell said most of the fields in the area were the same, with brown parts across the fields, mostly due to the drought. He reports that wheat in the area still has some potential — if the weather starts to cooperate from here on out and provides decent grain fill conditions.

In Rice County, Brian Sieker, who farms near Chase, said, “Wheat is just such a good thing in our rotation.” His early planted fields suffered the most from the freeze but are still his best fields despite that fact. Some of the late-planted wheat didn’t come up until January. His best-looking field was planted to KS Providence on September 18, 2023, but even it was only knee-high because of the drought. Sieker credited improved genetics for giving it the ability to weather the drought as well as it has.

“In February, we had some of the best wheat we’d seen in years,” Sieker said. “Hope’s not a good thing.” This year will be his third year in a row with an insurance claim on wheat, making him seriously question whether he can justify the cost of applying a fungicide.

In McPherson County, Derek Sawyer says his wheat had a lot more hope in February than it does now.

“It needs a rain,” he said. His area received 0.5 inch of moisture in April, but that’s 2.5 inches less than normal.

He said he wasn’t overly excited about planting last fall, but with fall rains in October and some moisture through the winter, it looked like his wheat showed promise. After freeze damage and drought, that promise is withering away, much like his wheat.

“There was not enough snow when the cold snap hit,” said Sawyer. “There’s always a storm that wipes out our hopes. It’s all too common lately.”

He reports that his wheat is going downhill very rapidly, and some is even having trouble shooting a head.

The loss of potential for the 2024 Kansas wheat crop has been a disappointment to all who saw promise this winter. There’s still time for Mother Nature to salvage what’s left with some optimal grain fill conditions. Participants in the Wheat Quality Council’s annual hard winter wheat tour will have a chance to take a closer look at this year’s crop during the week of May 13.

Marsha Boswell is vice president of communications for Kansas Wheat

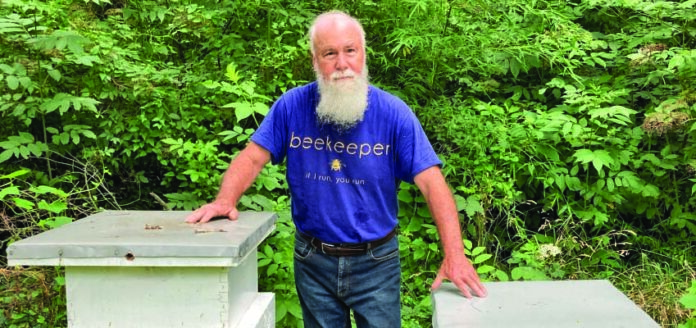

Kansas Beekeeper Works To Improve Urban Removal Of Colonies

Sheridan Wimmer

Kansas Living

Magazine

One thing you don’t expect as a homeowner is the possibility of a swarm of bees entering your home and taking residence. While they aren’t necessarily eating your food or using your utilities, these sorts of freeloaders can be a bit bothersome.

Instead of calling an exterminator, a Lawrence man suggests a different method of evacuation due to the decline in honeybee populations.

“I noticed bees in Lawrence were being killed by homeowners and with the steep decline of honeybees, I wanted to help provide a solution to both problems,” says Robert Brooks, who has a doctorate in entomology from University of Kansas and has been working with honeybees for more than 30 years.

A BEELINE FOR BOXES

Brooks is now in his second year of a two-year grant from the United States Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) Sustainable Research and Education Program to place swarm rescue boxes in 32 city parks in Lawrence.

“I had a swarm box every square mile of Lawrence’s 35-square miles,” Brooks says. “I caught 26 swarms in 2023 and 23 swarms the year before.”

The boxes in Lawrence’s city parks, which the City of Lawrence Parks and Recreation Department is supportive of, are aimed at having bees swarm there instead of between the floorboards or in the siding of Lawrence homes. When Brooks gets to a swarm box and sees bees, they are relocated to rural areas where they can pollinate sunflower or lavender fields and be made available to local beekeepers.

To keep the bees at a safe distance from people visiting the city parks, Brooks places the swarm boxes 12 to 15 feet up in trees. They are checked weekly and once a swarm arrives it is relocated to a double-walled insulated hive.

He wants to extend the program to other cities, and he has gained approval in Ottawa, a town about 30 miles south of Lawrence.

THE MOST FERAL OF THEM ALL

Where bumble bees and carpenter bees hibernate over the winter, honeybees don’t; they stay active inside their hives. Typically, when temperatures fall below 50 degrees, they’ll cluster together for warmth. Worker bees make sure to protect the queen by placing her in the middle of the cluster. But Kansas winters can get brutally cold, and some bees can’t acclimate as well.

“Most honeybees are not overwintering well with 30 to 80 percent dying each winter in Kansas for various reasons,” Brooks says. “The bees I work with are considered “mostly feral” and can survive the Kansas winters better than honeybees purchased from southern states.”

Winter loss is one cause of honeybee population decline over the years, but there’s been a steady decline since 2006. Honeybees represent an irreplaceable pollinator so researchers across the nation are working to improve populations and Brooks is providing part of the solution. Just in the U.S. honeybees pollinate $15 billion in agricultural products each year including more than 130 types of fruits, nuts and vegetables.

Kansas has seen the highest average colony loss rate between 2015 and 2022, losing one-fifth of state honeybee colonies each season. There are many causes for the decline, including mainly the parasite Varroa mite, which debilitates the overwintering bees. The only permanent solution is to find mite resistance in feral colonies.

The efforts made by passionate individuals like Brooks help to keep the agricultural economy running, one urban square mile at a time.

The next time a swarm of bees enters your home, consider reaching out to Brooks before you call an exterminator. They may not be the best roommates, but they’re vital to the many products they pollinate (plus honey).

Get more information about Brooks and his project at www.brookswildbees.com.Kansas Beekeeper Works To Improve Urban Removal Of Colonies

https://kansaslivingmagazine.com/articles/2024/04/01/kansas-beekeeper-works-to-improve-urban-removal-of-colonies

Property and taxes (2)

People can be inclined to view taxes this way: Impose them on someone else – the “fair share” principle of human nature. But our system of property taxation at times has lacked all fairness.

In the 1980s, property assessments in Kansas seemed a product of throwing darts at a board in the courthouse boiler room. The system lacked practical reasoning. Assessments (thus, taxes) were often wildly out of line with the actual market values of most property, from housing and businesses to farmland, factories and inventories.

Gov. John Carlin, a Democrat, recognized this distress and offered a cure, its centerpiece a constitutional amendment. The plan would classify property by use and assign it a value; assessment rates were fixed in various categories – utilities, agriculture, residential, businesses and so forth.

Carlin convinced (Republican) legislators that an amendment would accomplish two things:

‒ A massive, statewide reappraisal of all property;

‒ A fresh listing of property classifications with their assessment rates. The key classifications and rates included residential, assessed at 11.5 percent of market value; mobile homes, 11.5 pct.; personal property, 25 pct.; businesses, 25 pct.; utilities, 33 pct., and others.

One property classification was crucial: Farmland would be appraised by its ability to produce income and assessed at 30 percent. The political and economic impact of this section was so significant that the entire amendment, covering a dozen classifications, came to be known simply as the “use-value amendment.”

This is because the amendment – approved by voters in November 1986 – protects farmland assessments through use-value appraisal; taxes were (and are) determined by the income derived from the land, not by its market value. The amendment was to prevent owners from being forced to sell land simply to pay the taxes on it. It was a critical reform, exposing a glaring issue with property taxes, the chief component in funding local schools.

*

The property tax was bound in the Territorial Constitution in 1859 but the state income tax was not adopted until the early 1930s.

Although the income tax is a state charge, property taxes are tied to local control on the premise that friends and neighbors can manage their towns more reasonably than troublesome and costly bureaucracies. But today’s friends and neighbors are no longer apt to be tomorrow’s. Consider the disparities in property values across Kansas and the transience of Kansans today.

In contrast, income and sales taxes have supported on a state basis many programs such as welfare, Medicaid, and higher education. This ran counter to Gov. Brownback’s dream in 2011 of a state with no income tax, and with heavier reliance on the property tax.

The school finance reforms of 1992 had created a statewide uniform property tax for schools, a central pool for allocating the revenue and an aid formula to resolve wide disparities among districts’ property values. It ordered the burden of finance to be shared more equitably and revived the quest for a more balanced network of state finance.

Twenty years later, Gov. Brownback countered those reforms with his “Glide Path to Zero”, massive income tax cuts ultimately financed by heavy borrowing and by looting state agency funds, especially those at the Department of

Transportation (highways). Big business and high-bracket earners were delighted.

The Glide Path, embraced by the legislature’s heavy Republican majority, brought the state nearly to bankruptcy with billion dollar deficits and a quadrupling of state debt. The state corrected course in 2017 with the departure of Brownback and the election of pragmatic legislators who saw the difference between trickle-down dogma and reality.

(Next: rural schools)