The Ogallala aquifer that sustains parts of western Kansas has been declining rapidly, and some farmers want to take water from the Missouri River and route it west as a solution. The aqueduct would start north of Kansas City. But critics of the idea say it isn’t practical.

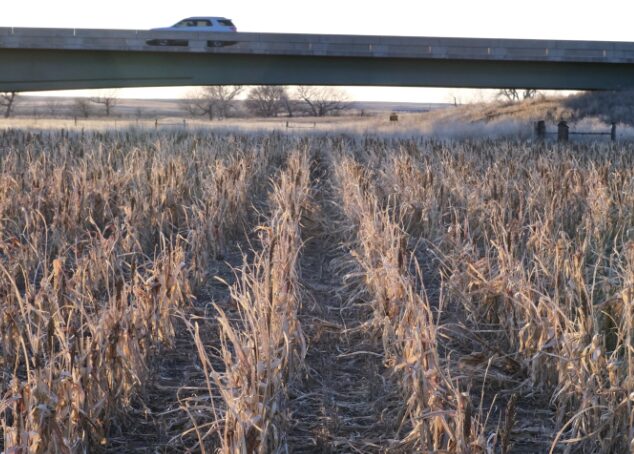

GRANT COUNTY, Kansas— Nature isn’t easy on farmers in western Kansas.

On a day when the temperature reached as low as -6 degrees, the frigid cold didn’t stop farmer Clay Scott. He still needs to get out and feed the cattle as a rare snowstorm is approaching his neck of the woods.

In between patches of snow lies arid land that sustains Scott and his family. Luckily, Scott farms wheat, corn and milo over the Ogallala aquifer, an underground source of water that has defined western Kansas, and supported the irrigation that turned the area into an agricultural powerhouse.

He is a multigenerational Kansan, and has spent years working the soil beneath him.

“I’ve got three boys that are coming back to the farm, and I want to give them the opportunities that I’ve had to grow and develop and prosper here on the High Plains,” Scott said.

But the only problem is, after pumping all that water for irrigation for the last 70 years, the aquifer is getting dangerously close to drying up. What’s more, there hasn’t been a lot of cohesive conservation projects pushed by the local Groundwater Management District.

A lot of individual farmers have spent thousands of dollars trying to irrigate the most efficient way, or convert some of their land to dryland farming. But the declines across the region still remain harsh.

Kansas Geological Survey hydrologist Brownie Wilson said that with a declining aquifer, there are really only two options for Kansans.

“You either got to quit taking so much water out, or you have to put more water in,” Wilson said.

Vocal leaders are more attracted to bringing in water as opposed to major structural changes to the region’s farming. They envision an aqueduct across the state that will bring water from the Missouri River. But critics of the aqueduct and similar plans say it’s not practical to bring in the water needed and is distracting people from the conservation efforts that could create a sustainable path forward.

Scott is one of the leaders supporting the aqueduct, serving on the Groundwater Management District 3 board. He formed the Kansas Aqueduct Coalition, with former district director Mark Rude, Chris Wilson and David Brenn.

They looked into a plan to draw flood water away from the Missouri river that separates Kansas and Missouri, all the way down to a reservoir in southwest Kansas to recharge the aquifer. That could allow more flexibility with how much water they use.

“If you look at other areas in the western United States, and see what they’re doing to combat their water demands, you see water aqueducts are vastly successful,” Scott said.

The Kansas Aqueduct Project

The idea of an aqueduct has existed for decades.

In the 1950s, farmers across western Kansas obtained thousands of water rights, giving them the right to pump water for irrigation.

By the 1980s, the reality of over pumping groundwater had already reared its ugly head. Congress, through the Federal Water Resources Development Act of 1976, authorized a study on groundwater depletion and the feasibility of a project to transfer water to western Kansas.

That would eventually become the idea of the Kansas Aqueduct Project. A 375-mile project across Kansas with 16 pumping stations.

To people like Scott, the aqueduct is the next logical step that secures the area’s economic future. But to critics, it represents an era of humans trying to control nature, which some argue doesn’t work anymore.

Burke Griggs has been a loud opponent to the aqueduct. He is a professor of law at Washburn University and specializes in natural resource law. He said the aqueduct cannot be built because too many people would need to approve it.

“Biggest reason is you’re going to have to cross about 300 miles of private property. If you look at the major water projects in the West, they’ve been built on land the United States owns,” Griggs said.

The aqueduct would also require a massive public investment, one that far exceeds even the $4.4 billion construction costs of the United States’ most expensive water transport system thus far, the Central Arizona Project. The costs for the Kansas aqueduct are projected to be roughly $20 to $30 billion.

Hydrologists are also concerned with the fact that projects from the Big Dam era of the 20th century are already struggling in Kansas because they are filling with sediment due to the lack of water and need investment to maintain their function.

Despite the hurdles, it hasn’t slowed down the support of the aqueduct among southwest Kansans or similar proposals to physically transport water to the region. Just a few years ago, the district gained attention for trucking 6,000 gallons of water across the state as a proof of concept. The water was then dumped on private land in Wichita County.

At water conservation meetings held last year by Kansas State University, residents brought up a similar idea of bringing water by rail to southwest Kansas.

But that focus on getting more water instead of conservation has had consequences. Hamilton County requested to leave Groundwater Management District 3. Hamilton County officials wanted to focus more on conserving their water.

Many are looking for solutions and ways to keep their water but also keep their towns growing.

A shift in conservation

Northwest Kansas has seen a revitalized sense of water conservation in the last decade after being the first district to adopt Local Enhanced Management Areas, or LEMAs.

It’s a program where farmers collectively volunteer to cut back on their water usage with the goal of achieving sustainable levels of pumping. Last year, the district’s water levels actually increased, proving conservation could work.

Groundwater Management District 4 director Shannon Kenyon has been another vocal critic of the aqueduct. She said that to her, it has been a distraction from the real water cuts that need to be made.

“It’s total fantasy land in my opinion. All smoke and mirrors,” Kenyon said.

Kenyon believes that the inaction by southwest Kansas led to HB 2297 being enacted into law last year. It requires all Groundwater Management Districts to submit an action plan to the state and be approved by June 2026.

Southwest Kansas has seen a more active attitude toward conservation since. They have held producer meetings throughout the towns trying to hear what farmers think should be done going forward to meet their goals.

Bret Rooney, another GMD 3 board member, spoke at the last meeting to make sure everyone understood the stakes.

“We’ve got a choice to either come together, figure out a solution, work on things, do things like we’re doing today,” Rooney said, “or someone from Topeka or Manhattan is going to tell us how we’re going to do it.”

These conservation attitudes are actually bringing more hope to southwest Kansas. The district only saw less than a foot of average water declines last year, and there’s hope they can capitalize on that momentum.

Kenyon said that she can feel the difference in leadership and attitudes all the way up in northwest Kansas.

“I am seeing conservation, attitudes, beliefs and projects being kicked into higher gear,” Kenyon said.

Culture of consumption

Georg Schaefer is a sociologist at the Max Planck Institute of Geoanthropology in Germany who studies Kansas agriculture.

He said agriculture is the foundation of society in western Kansas, and people want to protect that. He observes it can be easier to believe in an aqueduct than change your entire way of farming. But conservation would have a greater impact now.

“It was not born to be a distraction. It’s very compelling to get that techno fix,” he said. “It’s just cynical to propose it, because it will just make things worse in the long run.”

In a paper titled Ad Astra per Aquam, or “To the Stars through Water,” Schaefer outlined why ideas for an aqueduct remain persistent in southwest Kansas, and why water conservation is so difficult in that area.

Schaefer has studied western Kansas for the past several years. He said that water in western Kansas holds no intrinsic value. Rather, it’s given value by farmers as a way to grow crops and grow the local economies.

“Rather than work on how humans can adapt and fit into the natural environmental makeup of the region, the idea is the natural process should fit inside a human construct,” Schaefer said.

Looking at a map of western Kansas, a lot of the agriculture industry is condensed into southwest Kansas. There are feedlots, dairies, and beef packing plants all within less than 100 miles of each other, each containing thousands of cattle. Those herds need farmers to grow food for them and raise them.

A lot of farmers in southwest Kansas just can’t see a way out of the conundrum beneath them.

“We feel powerless, like the conservation efforts don’t have a payoff. It’s overwhelming on the people,” Schaefer said.