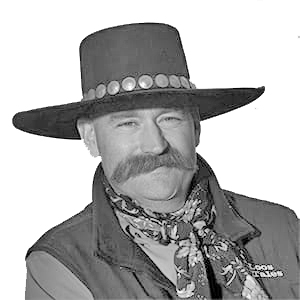

Roger Clark

Guest Columnist

I ran this route only a few times each year, and for the most part, it was a predictable run. It’s a scenic trip, even when the Flint Hills are on fire, and traffic is limited to road-weary families, triple-trailer rigs, drug-running entrepreneurs, and mail haulers like me. It’s a great time for personal reflection, corporate gratitude, and genuine appreciation for cruise control.

It’s a time to embrace mental health, goodwill to men, and remembering how good-looking my wife is. Life is good, some nights, and nobody knows it better than me. Especially at 3:00 AM when I’m just hitting the interstate, it’s a comfort zone for a mostly awake trucker.

That is, until I reached mile marker 100.1 north of Cassoday. By this time, I’m in that zone where one is groovin’ to the music, glancing at the moon, and counting the money that’s sure to roll in someday. But as I’ve done countless times on this run, I forget about the bridge. The evil bridge. The bridge that’s about to ruin the reputation I always wanted.

Bridges have expansion plates. Expansion plates, they like, expand. But these particular expansion plates, located only on the south side of the bridge, and only in the northbound hammer lane, have separated from the main structure. Running over it with a forty-thousand-pound semi is like cracking open a can of Bud Lite with a sledgehammer.

The impact launches me out of my state-of-the-art air seat and slams my chest against the shoulder belt. Anything not bolted down, including my coffee cup, cell phone, prepaid funeral plan, and Bluetooth headset are being slung around the cab like marbles in my wife’s state-of-the-art washing machine.

Some people believe time stops or goes into slow motion when things like this happen. They can recall seeing things like bright white lights, long-dead relatives, or images of the pearly gates. Some even claim to have died, briefly.

I should be so lucky. If I recall anything, it’s that trip last November, when I did the same #@%*^! thing, at the same #@%*^! bridge. But trust me, that recollection comes later, not sooner. In the moment, the only thing I’m seeing is the trailer logo way too prominent in the driver’s mirror.

Standing on the gas pedal like you would for a steer tire blowout, I drive for the shoulder and let the engine lug down before clutching. I might have practiced this before. But I also worry about being rear-ended in a situation like this, so I park straight, exit quickly, and do a one-minute walk-around looking for things that might be dragging on the ground, or broken. You know, like my pride for instance.

I did call the turnpike authority, just like last time, and they promised to get right on it, just like last time. I even write them an email about this one, and they responded by offering a prize if I can describe it in seven words or less.

So there’s hope, but not in Kansas. (And there’s my seven words!)

Later when it’s safe to do so, I find a good place to park and clean up the mess. Not only am I able to reset everything undamaged, but also find some loose change, leftover chicken nuggets, and the bonus check I lost last July.