A little red car trudges through dirt roads and dodges potholes before it zooms down the highway.

In the car is Isabel Yara and her daughter. Yara spent most of the early morning getting her daughter ready for a doctor’s appointment. But Yara lives in rural southwest Kansas, and seeing the doctor is about an hour’s drive.

She lives in Seward County and the closest town of Liberal has a shortage of medical professionals like much of western Kansas.

“Nearby we only have two options for the pediatrician, and the pediatricians here are completely booked,” Yara said.

With rural hospitals closing or perpetually understaffed, western Kansans often have to drive anywhere from an hour to multiple hours for doctor’s appointments. And fixing that for such a large area will be hard.

Yara had to look further to towns in neighboring counties. She remembers the struggle to get her daughter in for something urgent.

“There were times where she had gotten sick, and the closest option is urgent clinics, but they don’t work with children and it would be more expensive,” Yara said.

Rural Kansans on average travel twice as far for medical care than their urban counterparts.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have found that largely due to this difference in access to health care, rural residents are more likely to die early than urban residents. They’re also more likely to die from overdoses and suicide without quick access to emergency services.

And western Kansans pay the price with their health outcomes. According to the Kansas College of Osteopathic Medicine, rural Kansans are less likely to receive preventative care.

That also leaves them vulnerable to late stage diagnoses for cancer, heart disease and stroke, the main causes of death in rural Kansas.

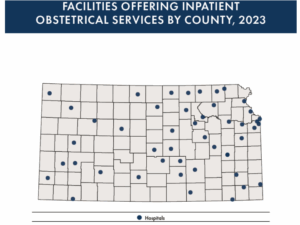

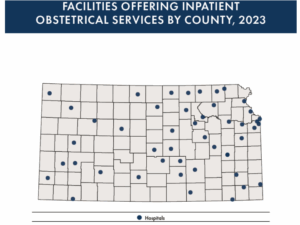

A Kansas Hospital Association analysis found many counties across western Kansas, patients aren’t able to stay in their home county for care.

A few hours away in northern Kansas, Beth Oller has seen this from the other side. She is a doctor that used to practice in Rooks County. She sums up rural living in Kansas pretty well.

“My closest Walmart was 50 minutes away, Oller said. “It’s not that surprising to also think that’s the closest place that you may be able to find medical specialists as well.”

Oller was on the frontlines of rural care, with patients coming from several counties over to see her. Norton, Graham, Osborne counties, even some patients from southern Nebraska.

But even if a county is lucky enough to have a physician or a specialist like Oller, it’s a hard workload to keep up with. Oller is a good example of why it’s so hard for communities in western Kansas to attract or keep doctors.

Oller, after years of practice, became the only doctor delivering babies in her county. She was always on call, and it made it hard to do her job at the clinic, and her job at home being a mother herself.

She made the hard decision to stop delivering babies which left the county in a maternity desert like much of western Kansas.

“It was a huge hit to me personally and very hard when I realized that I just couldn’t do it anymore,” Oller said.

Oller’s experience is quite common for medical professionals in rural Kansas.

Oller eventually needed to move back to eastern Kansas like many health professionals. She is the mother of four, and there weren’t enough education opportunities for her family. Like most western Kansas communities, living there isn’t always an easy sell.

But she still tries to treat her patients through telehealth. And now she is also traveling for health care, as the provider instead of the patient every four weeks to Rooks County.

But Karen Weis, the dean of the University of Kansas School of Nursing, looks at telehealth as a Band-Aid.

“Everybody thinks the solution is telehealth, but the problem is, there has to be a plan for making sure that the mother gets to the right place at the right time,” she said.

Weis is talking about the levels of care. The first level is primary care, family doctors and nurse practitioners. They refer patients to the second level of care. The second level is specialists, hubs with better equipped clinics in places such as Hays or Wichita. The third level is complex care that requires expertise and technology, often found in urban areas like Kansas City.

The Kansas Journal of Medicine conducted a survey to better understand barriers to access for rural health providers. Of the providers that participated, 75% of them said a lack of specialists close enough to them was the number one barrier when it came to patient referrals.

And Weis worries about this being a problem that only gets worse. The distance creates another problem for health care, which is communication. The survey found that to receive quality care, specialists need to access medical records, and getting those in a timely manner creates another obstacle in rural health.

“The people that review medical images should be the same people that say, ‘here’s the plan going forward’ for the patient,” Weis said.

So what are some of the possible solutions for creating more health care in rural Kansas?

That has been on the mind of Cindy Samuelson, the senior vice president of the Kansas Hospital Association.

She said rural hospitals always struggle to keep health care workers there. Working on an island without peers, and for less pay, is hard to overcome for rural communities. That’s the nature of a small, isolated town. There’s not as much money or resources for professionals.

Her main solution is for western Kansas to “grow its own health care workforce” by targeting those who already live there and have found community.

“We are looking at our middle school students, our high school students, and we’re trying to give opportunities to talk to them about how they may want to come back and be a part of this community,” Samuelson said.

But to fix the problem of rural health care in Kansas requires addressing other places where communities fall short.

Samuelson asked where will the new physicians live? Who will look after their kids? Where will their kids go to school?

These are hard questions without direct answers, but housing, day care and education are also part of the equation when it comes to getting more health care professionals to come work in the community.

But a more robust health care system also can be vital economically for a town on the frontier as well.

Cheyenne County in the corner of northwest Kansas is an example of a community with a more robust health care system.

Having those hospitals and clinics means more dollars for the county. It also means more jobs. For example, 90 hospital jobs within the county has a ripple effect of sustaining an additional 23 jobs in various industries.

“Partnering with other industries in a rural area is another way to try to recruit more health care workers.” Samuelson said. “Maybe those in the ag sector have a spouse that actually could work at the hospital?”

Calen Moore covers western Kansas for High Plains Public Radio and the Kansas News Service. You can email him at [email protected].