Still Time for Salad Garden

Hydrangea Blooms

The Rewilding of Kansas: Could Bison Return to the Plains for Good?

Imagine a time when the heartland of America pulsed with thunderous herds, the ground trembling beneath the hooves of millions of bison. This wasn’t just wild nature; it was a living, breathing ecosystem. Today, Kansas’ vast prairies whisper stories of those days, but most of the bison are gone, and the land has changed. Now, a bold question stirs: could the bison, icons of wild America, truly make a comeback and reclaim their ancient home? As the world yearns for wilder landscapes and a renewed balance with nature, the dream of rewilding Kansas with bison sparks excitement, hope, and a bit of controversy.

The Lost Giants of the Prairie

Kansas was once the kingdom of the American bison, with herds so immense that early settlers described them as “moving clouds” across the horizon. These animals shaped the tallgrass prairie, grazing patterns creating a patchwork of habitats that nurtured countless other species. But the 19th century saw the bison nearly erased from existence, hunted to the brink in a campaign that left only a few hundred survivors. The plains, once alive with the sounds and sights of bison, fell silent. The memory of these giants lingers, however, and their absence is felt in the very rhythm of the land.

Why Bison Matter to the Kansas Prairie

Bison are more than just big animals; they’re ecosystem engineers. Their grazing habits encourage plant diversity, prevent the spread of woody shrubs, and create open spaces where wildflowers and grasses can flourish. Unlike cattle, bison move constantly and graze selectively, which benefits soil health and helps native plants thrive. Their wallows—shallow depressions they create by rolling in the dirt—collect rainwater and become mini-habitats for insects and birds. Restoring bison could mean reviving the very soul of the Kansas prairie, bringing back the intricate web of life that once depended on them.

The Science Behind Rewilding

Rewilding isn’t just letting animals loose and hoping for the best. It’s a carefully planned process that uses scientific research to guide every step. Scientists study how bison interact with plants, soil, and other animals, and how their behaviors influence the landscape. Ecologists also monitor changes in plant species, water cycles, and even fire patterns, since bison grazing can reduce the risk of wildfires. By understanding these dynamics, experts can design rewilding projects that boost biodiversity, restore ecosystem functions, and increase the land’s resilience to climate change.

Challenges to Bison Reintroduction

Bringing bison back to Kansas isn’t as simple as opening a gate. Modern Kansas is a patchwork of farms, towns, and highways, with most land privately owned. Bison need large, connected areas to roam, but fencing and development make this difficult. There are also concerns from ranchers about disease transmission to cattle, potential competition for grazing, and property damage. Overcoming these obstacles requires collaboration among landowners, conservationists, and local communities, as well as creative solutions like wildlife corridors and shared land management.

Current Efforts and Success Stories

Despite the hurdles, some bold projects have already begun. The Konza Prairie Biological Station and the Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve are two places in Kansas where bison have been reintroduced with promising results. These herds are carefully managed, and researchers closely monitor the impacts on the ecosystem. Over time, native grasses and wildflowers have rebounded, and rare birds and insects have returned. These successes fuel the hope that larger-scale rewilding is possible, and that the bison could one day roam more freely across the state.

Bison and the Climate Crisis

The return of bison to Kansas could play a surprising role in fighting climate change. Healthy prairies store vast amounts of carbon in their deep roots, and bison grazing helps keep these grasslands vibrant and productive. By preventing overgrowth and encouraging new plant growth, bison help the prairie capture more carbon from the atmosphere. This natural climate solution is gaining attention as the world searches for ways to slow global warming, making bison restoration not just an ecological dream, but a practical strategy for the future.

Community Voices and Cultural Connections

The bison’s story is deeply woven into the cultural fabric of Kansas, especially for Indigenous communities who have long revered these animals as sacred. For many, the return of bison isn’t just about restoring nature—it’s about healing historical wounds and reviving traditions. Community-led projects are helping to reconnect people to the land and to each other, using bison as a symbol of resilience and renewal. As more people rediscover the bison’s significance, support for rewilding efforts continues to grow.

Economic Impacts: Risks and Rewards

Rewilding bison isn’t just about nature—it also has economic consequences. On one hand, bison herds can attract tourists, create jobs, and open new opportunities for eco-friendly agriculture. On the other, landowners worry about property rights, livestock safety, and potential costs of managing wild animals. Balancing these interests is tricky, but some ranchers are finding ways to coexist, raising bison for meat or ecotourism and benefiting from conservation programs. The path forward will require compromise, innovation, and a willingness to see value in wildness.

What Would a Wild Kansas Look Like?

Picture a Kansas where the prairie sways with native grasses, where butterflies and birds dart through blooming wildflowers, and herds of bison move across the horizon like living storms. Such a vision is both inspiring and daunting. Restoring wildness means accepting change and uncertainty, but it also promises beauty, resilience, and a deeper connection to the land. For many, the thought of bison returning for good is a symbol of hope—a reminder that even after great loss, nature has the power to heal and surprise us.

The Road Ahead: Hope, Hurdles, and Possibility

The journey to rewild Kansas with bison is filled with both hope and complexity. Scientific research, community engagement, and creative problem-solving are pushing the dream forward, but challenges remain. The question isn’t just whether bison can come back, but whether people are ready to welcome them home. The future of the Kansas prairie may depend on our ability to see ourselves as part of the wild story, not just observers or managers.

Bison once shaped the fate of the plains—could they do it again?

By Maria Faith Saligumba

2 Kansas Horses Test Positive for WNV

On August 8, two horses in Kansas were confirmed positive for West Nile virus (WNV), including one horse in Barber County and one horse in Reno County.

EDCC Health Watch is an Equine Network marketing program that utilizes information from the Equine Disease Communication Center (EDCC) to create and disseminate verified equine disease reports. The EDCC is an independent nonprofit organization that is supported by industry donations in order to provide open access to infectious disease information.

WNV 101

West Nile virus is transmitted to horses via bites from infected mosquitoes. Not all infected horses show clinical signs, but those that do can exhibit:

- Flulike signs, where the horse seems mildly anorexic and depressed;

- Fine and coarse muscle and skin fasciculation (involuntary twitching);

- Hyperesthesia (hypersensitivity to touch and sound);

- Changes in mentation (mental activity), when horses look like they’re daydreaming or “just not with it”;

- Occasional drowsiness;

- Propulsive walking (driving or pushing forward, often without control); and

- Spinal signs, including asymmetrical weakness; and

- Asymmetrical or symmetrical ataxia.

West Nile virus has no cure. However, some horses can recover with supportive care. Equine mortality rates can reach 30-40%.

Studies have shown that vaccines can be effective WNV prevention tools. Horses vaccinated in past years need an annual booster shot, but veterinarians might recommend two boosters annually—one in the spring and another in the fall—in areas with prolonged mosquito seasons. In contrast, previously unvaccinated horses require a two-shot vaccination series in a three- to six-week period. It takes several weeks for horses to develop protection against the disease following complete vaccination or booster administration.

In addition to vaccinations, owners should work to reduce mosquito population and breeding areas and limit horses’ mosquito exposure by:

Local first responders’ input addresses lessons from DeBruce explosion

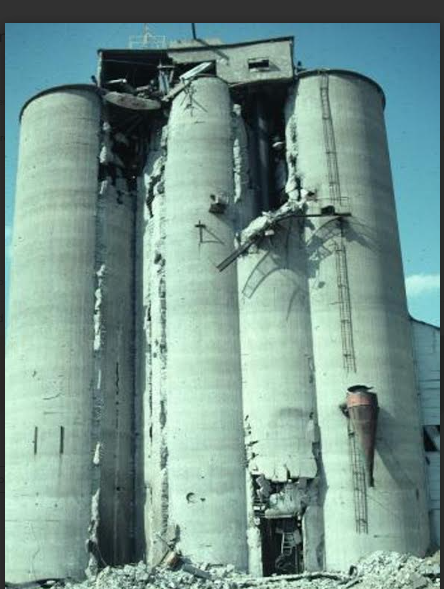

Even on a global scale, the impact of the DeBruce grain elevator explosion

(considered the largest such facility at the time) in Haysville back on June 8,

1998, was felt — and certainly hit close to home in Derby and the

surrounding area.

Local residents Larry Simmons and Malissa Paxton, father and daughter,

were among those first responders on scene at the explosion— quickly

jumping into action.

“I didn’t really notice it. I notice every explosion around me now —

earthquakes and everything — but [my partner] said, ‘What happened?’ He

had that walkie in his ear and immediately he was like, ‘Wow, something

big’s going on,’” said Paxton, who was working for Sedgwick County EMS at

the time. “You don’t forget that. And before that, it was just a building I

didn’t know anything about.”

“We knew that it was something big and we figured [out] what it was before

dispatch even gave any information; we knew,” said Simmons. Now retired,

Simmons was working for Sedgwick County Fire Department at Station 38 in

Bel Aire at the time.

Currently, Derby area resident Robin Turnmire — who lost a brother in the

DeBruce explosion — is working on a documentary film, “11 Days,” that tells

the story primarily from the first responders’ perspective.

Noting that she never actually set out to make a movie, Turnmire became an

“accidental filmmaker,” as she was looking to shed light on the instigating

factors of the explosion as more of a preventative measure.

“What I set out to do was get to the truth about what really happened out at

DeBruce, and then go figure out how to do the causal analysis and really dig

in,” Turnmire said.

Identifying the first responders as the most accurate witnesses, Turnmire set

out to talk with them about their experiences “rolling up to a war zone,” as

many of them put it. Turnmire talked to over 25 of the 200 first responders

who were on scene in the immediate aftermath of the explosion, which is

considered one of the deadliest in American history and claimed the lives of

seven workers.

Once she began interviewing the first responders, she realized their stories

had to be captured on film. Among those she talked to were the firefighters who rescued her brother, Lanny Owen, from being trapped near the top of

the grain elevator. Their efforts gave him 11 more days to live, which is

where the film gets its title.

Recalling the scene

Simmons was also among those first responders Turnmire talked to for the

film. He was a captain with Sedgwick County Fire at the time and in charge

of the technical rescue team.

As Simmons recalled, “the whole tops of the elevators were gone and people

were hanging in the headhouse [the top two to five stories].” That left

Simmons with quite the situation to sort out, first calling in a rescue

helicopter to help the trapped workers. However, the vibrations from the

blades were dislodging rubble and creating more issues, so cranes were

called in instead to get the technical rescue team up to the trapped workers

to help free them.

Looking back, Simmons noted his team had done all sorts of rescues over

the years, but responding to the DeBruce explosion combined all of those

elements into one call and he said the imprint of the body of one of the

victims 100 feet up on one of the silos has stayed with him, speaking to the

force of the blast.

“When I saw that body up there, that just blew me away,” Simmons said.

On top of that, Simmons and his team had to worry about the additional

risks of secondary explosions while on site. He stayed on in response until

the morning after the explosion, while his daughter was out there for the

day providing medical support to the firefighters while also helping search

the scene for critical body parts — with recovery and cleanup efforts

continuing for weeks after.

Now a physician’s assistant at Tanglewood Family Medical Center, Paxton

said she and her father were aware they were at the same scene the day of

the explosion. While their paths didn’t cross, given how shaken the

firefighters she treated were, she was certainly concerned.

“I knew that he was in command of that scene, and I was worried,” Paxton

said. “It was a threatening scene and I knew he had a lot of stress on him,

and those firemen were his family. He had to make decisions on who was

going in; he was in a tough spot.”

Avoiding future risk

Rob Dusenbery, a fellow retired firefighter who now teaches fire science at

Wichita South High School, noted there are only a handful of calls the

magnitude of the DeBruce explosion firefighters will make in their careers.

Part of the purpose of the film is to help raise funds for Dusenbery’s program

and other local firefighter charities.

While Dusenbery was relatively new to the department compared to

Simmons and was on the fringes of the response team, the lessons on

incident management — between all parties — from the grain elevator

explosion are something he is trying to pass on to the next generation within

the consistency he preaches to his students.

“We start out with a good game plan and then we make a mistake and don’t

correct it and pretty soon we’ve normalized that behavior. Pretty soon we

normalize other mistakes and other sloppiness, and when you end up on an

accident scene like that somebody has to have their stuff together and

somebody else has to know what their place is and how they react,”

Dusenbery said. “I see something like DeBruce as the ultimate example of

that kind of coordination, and I see something like this film as a way to get

people to think about it.”

Speaking to the many moving parts of such a response, Simmons noted he

was just one pawn out on the scene doing his job and there are plenty of

others who deserve the spotlight — which the film is shedding some light on.

“It was overwhelming. It’s something I’ll never forget in my life,” Simmons

said. “I learned a lot from it, and I’m sure other people learned a lot from it

that were there.”

There were signs of an eventual issue like the explosion. Simmons saw it

when he worked at the grain elevator as a teenager, and Turnmire said her

brother made comments noticing issues coming to a head as well.

Part of the drive behind the film is to explore the technical challenges,

hazards, lessons, etc., from the DeBruce explosion and other similar

accidents to help prevent them in the future.

“I can’t bring my brother back. I can’t bring those men back. None of them

are going to come back. We’re not going to have any of those experiences

with them, and I am so sorry that they’re gone,” Turnmire said. “But on the

flip side, I’m so thankful that I’ve had this experience with the [surviving

responders].

“This is about risk management. I’m hopeful that by having these

conversations, we educate [people] that it’s all of our jobs,” she continued.

“What can we do as a community to make sure it never happens again?”

Currently, “11 Days” is in post-production and editing, with a private premier

screening being planned for the contributing first responders. Turnmire is

also seeking to enter the film on the festival circuit in the coming months.

For more updates and to view the film’s trailer, check

https://sannnordstudios.com/11-days-the-film/.

Derby’s Larry Simmons (right) and Malissa Paxton, father and daughter, were among the

emergency personnel who responded to the DeBruce explosion, helping share some of their

insight for the documentary.

Documentary,

BY KELLY BRECKUNITCH

[email protected]