A small, lakefront cove provided a pleasant place to swim, fish and ice skate not far from the house where B.D. and Mary Ehler moved their family in May 1976 at Osage County’s Pomona Lake.

The water in the cove stood 5 to 7 feet deep, recalled B.D. Ehler, now 90, who still lives there with Mary Ehler.

About six docks stood along the cove, with most residents using walking paths to get there, Ehler told The Capital-Journal on Sept. 9.

“It was a pretty decent-sized cove,” he said. “But eventually, it started silting in.”

Today, that cove is gone.

Its former entrance is completely covered by silt, a fine type of sand, clay, or other material carried by running water and deposited as sediment. The cove’s docks have been long since removed.

The cove’s only remnants that could be seen Sept. 9 were a shallow inland pond, a broken tackle box, an iron bar that appeared to have been part of a gate and a U.S. Army Corps of Engineers marker, which stood where a dock would have extended to the water’s edge.

How much water supply has silt cost Kansas reservoirs?

The cove’s fate helps illustrate how silt coming from upstream has hurt Kansas reservoirs in ways that include reducing their storage capacity and available recreation space.

Reservoirs have lost more than 400,000 acre-feet of “water supply stored” to sedimentation, according to the Kansas Water Office’s 2022 Kansas Water Plan. An acre-foot is 328,581 gallons, according to a graphic included in that plan.

Tuttle Creek Reservoir in Riley and Pottawatomie counties has been hit hardest, losing more than 200,000 acre-feet to sediment, with roughly 225,000 acre-feet in projected water supply volume remaining, that graphic said.

How do reservoirs lose storage capacity to silt?

The state of Kansas is home to 24 large, man-made reservoirs, all built by the federal government between 1940 and 1982

Those reservoirs continually lose storage capacity to sedimentation from upstream waterways, the water plan said.

“Lands within the watersheds of reservoirs lose soil, which is then transported to the reservoirs as a result of varied precipitation events,” it said.

Soil becomes trapped in the reservoirs, reducing available water supply, the plan said.

Couple drove across bottom of Pomona Lake before it became a lake.

B.D. and Mary Ehler, who both graduated in 1952 from Topeka’s Highland Park High School, recalled how, in about 1963, they drove in a 1958 Ford Thunderbird across what would later become the bottom of Pomona Lake.

That lake then opened in 1964.

An avid fisherman, B.D. Ehler is retired as director of pharmacy services for Topeka’s Menninger Clinic. The Ehlers and their three children moved from Topeka to a house just south of Pomona Lake in 1976.

That reservoir has effectively controlled flooding downstream but has increasingly silted in over the years, Ehler said.

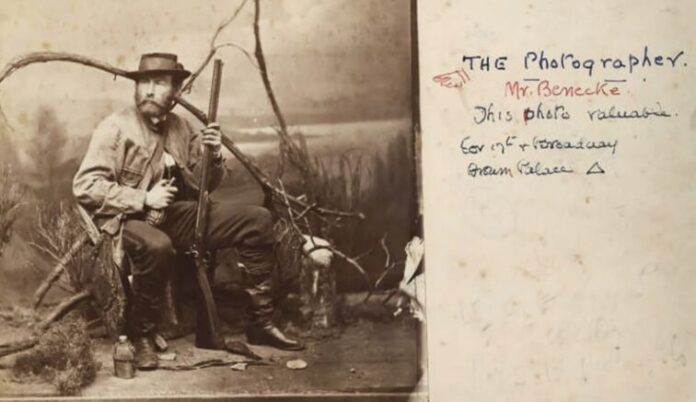

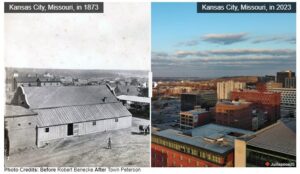

He showed The Capital-Journal photos illustrating how the cove near his home grew smaller as time passed.

The Army Corps of Engineers knew that was going to happen, Ehler said.

“The corps anticipated when they built this reservoir that in 50 years it would be 50% silted in,” he said.

Laura A. Totten acknowledged this past week that when the Kansas reservoirs were built, the Army Corps of Engineers made estimates regarding the specific lifespans each would see.

Those estimates took into account the effects of sedimentation as well as the lifespan of the lake infrastructure, said Totten, who is project manager and planner for the corps’ Kansas City, Missouri, District.

Many of those reservoirs are doing better than was anticipated, Totten said.

At Pomona Lake, water supply storage lost to sedimentation amounts to less than half the projected water supply volume remaining, according to a graphic that’s part of the 2022 Kansas Water Plan.

Still, the years have taken their toll on those reservoirs, that plan said.

“With many of these reservoirs now over 40 years old, recent and historic bathymetric surveys are showing that reservoir storage capacity is being lost in a trend similar to the initial projections for several Kansas river basins,” it said.

The plan added: “There is a projected and observed loss of storage as sediment carried by inflowing rivers and creeks is trapped within the reservoirs, with some Kansas reservoirs trapping over 98% of the sediment carried from their upstream watersheds. Future conflicts may arise where the amount of water able to be retained in reservoir storage will be insufficient to meet the demands of multiple user groups and puts the state in the position of being unable to supply adequate amounts of water for anticipated future uses.”

Here’s what a ‘Blue Ribbon’ task force says needs to be done.

The Kansas Water Plan noted that a state-created Blue Ribbon Funding Task Force in 2015 put out a report sharing its long-term vision for the future of the state’s water supply.

That report concluded the state must adequately reduce sedimentation rates to protect future water supply, and identified “a funding need of $21 million per year to support conservation and remediation activities to secure future reservoir water supplies,” the water plan said.

It said the state needs to more effectively:

- “Quantify the sedimentation issue through updated reservoir bathymetric surveys and surface water monitoring where feasible.”

- Identify alternative sediment, nutrient, and basin management strategies to reduce impacts to reservoirs, while avoiding downstream impacts.

- And “gauge and identify if the reservoirs are losing storage capacity at rates as initially projected and potential changes to these rates from behavioral changes within the watersheds.”

Steps have been taken upstream from Kansas reservoirs to help deal with silt problems, the water plan said.

“Targeted investments have included implementation of best management practices such as streambank stabilization projects, watershed dam construction, and increased support for soil health initiatives,” it said. “However, the acres of agricultural lands that have had conservation practices implemented and the number of streambank stabilization sites completed, with past and current levels of funding, have not remediated reservoir sedimentation issues.”

Corps of Engineers official: Sediment problem is being tackled.

Much is being done otherwise to mitigate silt-related problems in Kansas reservoirs, Totten said.

She manages a project for which the Army Corps of Engineers plans beginning next spring to do $6 million worth of dredging at Tuttle Creek Reservoir, where pressurized water will be used to lift sediment from the base of the lake and push it downstream into the Kansas River.

Totten said other steps being taken include:

- Forming the Kansas Reservoir Sedimentation Task Force — made up of representatives from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Kansas City and Tulsa districts, the Kansas governor’s office and the Kansas Water Office — which began meeting in January to find solutions for dealing with sedimentation in reservoirs across the Kansas River Basin.

- Recently completing a Kansas River Reservoirs Flood and Sediment Study, “a watershed study which included extensive work related to this issue and the impacts it causes to the multiple uses of our reservoirs such as water quality, water supply, recreation, flood control, etc.”

- And initiating multiple “planning assistance to states” studies through which the Army Corps of Engineers and the state of Kansas are investigating the issues and determining recommendations for managing sediment.