Sumner County approves wind farm agreements

Wild Plains Wind will pay $1 million a year in lieu of taxes

By Duane Schrag

Special to the Rural Messenger

A 98-turbine wind farm that is to be located between Oxford and Wellington is moving forward after Sumner County officials last month signed an agreement with Wild Winds Energy Project LLC that would give the county upwards of $1 million a year in lieu of taxes.

The project has a lifetime waiver from property taxes because it obtained a conditional use permit for the project from Sumner County in October 2016, months before state law was changed to limit property tax exemptions for such projects to just 10 years.

Without an exemption, Wild Winds Energy Project would have incurred a property tax bill of an estimated $117 million over 30 years, or an average of nearly $4 million per year.

Sumner County issued the permit even though the wind developer’s application did not contain a plan for decommissioning the turbines, or an agreed-upon financial guarantee. Rather, the developer promised to enter an appropriate agreement and provide financial assurances at some time in the future.

County regulations state that among the documents that “shall be submitted at the time of the application” are “a decommissioning plan describing the manner in which the [project] will be dismantled and removed from the site at the end of its useful life” and “an Escrow Account/Surety Bond/Insurance Policy in an amount approved by the Board of County Commissioners.”

County Clerk Debra Norris said in an email last week that no decommissioning agreement has yet been submitted for the commission’s consideration.

Annual payments to the county will start at $750,000 and increase by 1.5% each year. According to the schedule contained in the Payments in Lieu of Taxes (or PILOT) agreement, the total to be paid to Sunmer County over the course of 30 years would be $28.2 million.

In addition to the payments to Sumner County, three school districts are to each receive $25,000 annually under the PILOT agreement: Belle Plaine USD 357, Oxford USD 358 and Wellington USD 353.

A spokesman for Tradewind Energy, the parent company of Wild Winds Energy Project, declined to answer questions about when construction is to begin, how long it will take, and how much it will cost. Current estimates are that commercial wind projects cost about $1.5 million per megawatt of generating capacity, or a total cost of about $450 million for this project.

According to Tradewind’s website, the 300 MW project will encompass about 25,000 acres and involve around 120 landowners.

Sumner County officials also signed a second agreement with Wild Winds Energy Project on Feb. 12. Under the agreement, Wild Winds will post a $3 million guarantee that roads will be returned to the condition they were in before project construction started. All non-passenger construction-related equipment will be allowed only on specified routes.

In March 2018, Wild Winds Energy Project asked the FAA to review the placement of 98 wind turbines on either side US-160 between Oxford and I-35. The proposed height of the turbines is 660 feet – the tallest so far approved in Kansas, and 30 feet taller than the St. Louis Arch.

The FAA determined in August 2018 that the turbines are not a hazard to aircraft.

***

March 20, 2019

A wind farm proposal simmers in Reno County; permit hearing April 4

By Duane Schrag

Special to the Rural Messenger

Matt Amos has seen more conflict than anyone ever should. He’s been deployed to both Iraq and Afghanistan.

But what’s happening now in bucolic rural Reno County deeply troubles him.

“We can’t let this project define us and divide us,” says Amos, a retired Marine who lost both his legs after he stepped on an IED in Afghanistan eight years ago.

Ironically, the project is one that many associate with progress, with forward-thinking, with being part of the solution to one of humans’ most intractable problems: combating climate change.

The project Amos refers to is Pretty Prairie Wind Farm, an 80-plus turbine wind farm being proposed by one of the world’s largest developers of renewable energy, NextEra Energy, based in Florida. NextEra owns and operates seven wind farms in Kansas, including the state’s first wind project, which was constructed in Gray County in 2001.

Pretty Prairie Wind Farm is to be located in the southeast corner of Reno County – south of Haven and occupying the countryside to the east of Cheney Reservoir.

NextEra says it is working hard to be a responsible, considerate player.

“We operate more than 120 successful wind farms across the United States and Canada, and we wouldn’t be able to do so if we didn’t do it responsibly and in partnership with landowners,” wrote Conlan Kennedy, a spokesman for NextEra.

Profits from NextEra and its affiliated companies (it owns Florida Power and Light, for example) have assets valued at $103.7 billion, and in 2018 posted profits of $5.8 billion.

He expressed dismay at the fierce opposition that erupted over the past 15 months.

“There is a vocal minority in the area that has been spreading misinformation about the project,” Kennedy said in an interview. “It’s a shame that the few would resort to fear-mongering about an industry that has done such good not only for our country but especially Kansas and the Kansas economy.”

The “vocal minority” is spearheaded by Reno County Citizens for Quality of Life, a loose-knit group of volunteers dedicated to, if not out-and-out stopping the project, then gaining concessions that address their concerns.

They have been producing overflow crowds at Reno County commission meetings for months. More than 100 showed up for an information meeting Feb. 24 in St. Joseph Ost Parish Hall, in the far southeast corner of the county. Their concerns have much in common with those expressed by opponents to wind farms elsewhere in the country, including:

– Landscape changes caused by 500-foot tall turbines (the Epic Center in Wichita is the state’s tallest building, at 385 feet to the tip of the antenna on its roof);

– Noise from the turbine blades;

– Shadow flicker from the rotating blades;

– Infrasound (inaudible pressure waves caused by the moving blades);

– Light pollution at night from the blinking red tower lights;

– Reduced market values for surrounding property;

– Gag orders in landowner contracts that stifle complaints about these harmful effects.

These phenomena in turn give rise to many complaints. Some are aesthetic; others allege physical harm. Many of the health claims are challenged in peer-reviewed literature. And always lurking in the wings is the question of what regulations should be imposed to protect area residents.

Zoning

Perhaps the most widely used regulatory tool is zoning, a framework that establishes a hierarchy of land uses – agricultural, commercial, residential, industrial, etc. – and within each specifies the activities that are allowed. In many zones, certain activities are allowed only after a special use permit or a conditional use permit has been issued. This restriction gives local governments the opportunity to review such cases and, if necessary, impose certain conditions before authorizing the activity.

A fundamental regulation found in zoning regulations is the setback – the minimum distance between, say, a home and the property line, a buffer that helps ensure that the home on one parcel doesn’t unduly affect the neighbor.

County commissions have the legal authority to adopt zoning regulations in the county. But Midwesterners have an independent streak, and about half the counties in Kansas are not zoned. The owners of unzoned property may build anything, anywhere, so long as it is within their property lines.

Reno County has zoned some parts of the county, but not many. About two-thirds of the unincorporated area is unzoned.

“Zoning in Reno County generally is not very popular,” says County Counselor Joe O’Sullivan. “It is known for being extremely controversial.”

So Reno County commissioners have historically let residents take the lead.

“Zoning has been extended incrementally when constituents wanted it to be done,” O’Sullivan says.

One of the places constituents had not asked for zoning is in the southeast quadrant of the county. There is a zoned area several miles deep surrounding Cheney Reservoir, but otherwise all the unincorporated areas in that corner of the county are unzoned.

The upshot is that some of the area where NextEra wants to put turbines is zoned, some is not. Strictly speaking, NextEra is free to put turbines anywhere on the land of a consenting owner whose land is not zoned.

In the areas where there is zoning, the county has a handful of regulations relating to commercial wind farms:

– Turbines must be set back from public roads and property lines by the total turbine height plus 50 feet, but never less than 500 feet;

– Turbines must be at least 1,000 feet from the home of anyone who doesn’t have a turbine on their property;

– The wind developer must maintain $1 million liability insurance.

As a practical matter, NextEra has pledged to abide by 2,000-foot setbacks to the homes of non-participating residents, twice the required distance. And it has further said it will abide by the county’s zoning regulations throughout the project, regardless of whether a particular spot is actually zoned.

Permit hearing April 4

But in addition to these setbacks, the wind developer must apply to the county for a conditional use permit. Before a permit is issued the planning commission must hold a public hearing. It then recommends to the county commission that the permit be approved or denied, and the county commission makes the final decision.

The planning commission’s public hearing for NextEra’s conditional use permit will be at 3 pm April 4 at the Atrium Hotel and Convention Center, 1400 N. Lorraine, in Hutchinson.

Setbacks can have a profound effect on the arrangement of wind turbines and have been a hot topic.

“We are obviously very concerned with setbacks of turbines from residential homes and non-participating properties,” Amos says. “A lot can be solved with setbacks. And the one thing we as a group want to relay to everybody – we are not anti-wind. We know that wind has its place. We just want it to be done responsibly. And the way the county has so far tried to make this happen, it has not been responsible at all.”

In particular, the group was angered by O’Sullivan’s admonition that the county commission stop taking testimony on the subject until the public hearing in April. Commissioners had been allowing residents to speak on the subject during meetings, under the agenda item set aside for topics not on the agenda.

“We want our voices to be heard,” Amos says.

O’Sullivan says their voices will be heard, but it’s important the county follow the law. In Kansas, county commissioners have three hats to wear: administrative (deciding which roads are paved this summer), legislative (adopting rules for county operations) and quasi-judicial.

“They are the final authority on implementing zoning regulations, and when they do that, they act in a quasi-judicial capacity,” O’Sullivan says. “When you are talking about regulating the uses of land, and anybody’s free use of land, and the government’s doing it, there’s certain due process involved, and the courts have said that’s a quasi-judicial decision. Therefore, there are certain standards that need to apply, because those decisions are appealable to the district court.”

Among those standards is the requirement that decisions be made solely on the evidence presented on the matter.

“The record of evidence begins with the filing of an application for a conditional use permit,” O’Sullivan explains. Residents who live within 1,000 feet are formally notified of the scheduled hearing, but anyone can attend and testify.

“The notice of hearing tells people comment is welcome,” he says. “It can be presented in writing at any time before the hearing, or they can appear at the hearing. All of that constitutes the record upon which the planning commission is required to make its recommendation, and the evidence that they consider has to be part of the record and not extraneous to it.”

***

March 27, 2019

A wind farm bill dies; challenges continue

By Duane Schrag

Special to the Rural Messenger

When word that House Bill 2273 had been introduced in the Energy, Utilities and Telecommunications committee last month, it took some people by surprise. News arrived by the grapevine.

“We got word that it had been filed late Wednesday evening when (the Kansas Healthcare Collaborative) notified our county health officer on a routine matter,” said Reno County Counselor Joe O’Sullivan. “The time limit to submit written testimony was Friday at noon.”

The bill was of particular interest to Reno County residents. NextEra Energy, a Florida-based company that bills itself as the world’s largest developer of renewable energy, was poised to apply for a conditional use permit to build a wind farm in southeast Reno County.

News of the plans had ignited a firestorm of protest from citizens in that part of the county. For weeks during the final months of 2018 they packed county commission meetings to voice their objections.

And now, seemingly out of the blue, a bill materialized in the House energy committee that was, in O’Sullivan’s words, “designed for one thing, and that is to shut down wind energy.”

The chairman of the committee is Rep. Joe Siewert, who lives in southern Reno County (see related story).

What followed over the next few days amounted to a hastily staged skirmish over wind development in Kansas. The committee took testimony supporting the bill the following Tuesday (Feb. 19); it heard from opponents on Thursday.

By Friday, the bill was dead.

It seems unlikely, however, that the war over how to situate wind farms in Kansas is over. Many of the claims made by both sides don’t hold up under scrutiny. And with mounting evidence of the profound disruptions caused by climate change, it’s virtually certain that pressure to bend the arc of energy production away from carbon-based fuels will only grow.

* * *

While there were expansive disagreements over the merits of the bill, there seemed to be no disagreement on one central point: the bill, if enacted, would make sweeping changes.

Perhaps the most notable aspect of the bill was that it would have established setbacks – the minimum distance from the turbine to the nearest home or public building – of a mile and a half. Typically, setbacks are roughly a quarter mile; the setbacks for the proposed Pretty Prairie Wind Farm in Reno County are 2,000 ft. or just over one-third of a mile.

Several representatives of the wind industry said the setbacks were so onerous they would effectively kill wind development in Kansas. A spokesman for NextEra testified that none of the seven wind farms developed by NextEra in Kansas would have been built if setbacks of 1.5 miles were required.

Half the counties in Kansas have no zoning regulations, and supporters of the bill claimed that this made them easy prey for wind developers.

The wind industry countered that even in unzoned counties, county commissioners can block wind projects that don’t meet their approval. A wind industry lobbyist cited agreements for decommissioning (removal of turbines when they are no longer used), road maintenance and payments in lieu of taxes.

“So those three agreements are the opportunity for the county – in an unzoned county – to have final approval authority over whether a wind farm is actually going to come into a community,” lobbyist Kimberly Gencur Svaty testified. “If the county doesn’t sign off on either one of those three agreements, even though the county is not zoned, the wind project will not move forward.”

But Svaty said after the meeting that there is no state law granting counties authority to block wind farms if developers don’t sign one of those agreements.

The Kansas Supreme Court has upheld the right of counties to declare a moratorium on wind farms.

Sedgwick, Wabaunsee and McPherson counties have moratoriums in place, and Reno, Marion and Nemaha counties have all discussed them.

Perhaps the most dramatic testimony against HB 2273 came from Alan Anderson, an attorney with Polsinelli, a law firm with offices across the United States. His written testimony bristled with a long list of the bill’s shortcomings. It would purportedly violate the Kansas Constitution, the County Home Rule Act, and the Kansas Zoning Enabling Act.

On top of that, it implicates the state and federal constitutions, “it tramples on the goals of essential due process protections for landowners and their property rights”, violates the freedom of contract, creates regulatory uncertainty, harms the state’s ability to compete in business, substitutes local experience and expertise for bureaucratic fiat (he probably meant the opposite), and is so vague as to be unworkable.

This landslide of imperiling legislation seemed to overwhelm at least some committee members.

“My basic problem is the constitutional aspect of this,” said Rep. Anne Kuether, ranking minority member. “I just can’t go along with this. I think the whole bill is just basically flawed. This is clearly questionable on constitutionality.”

That’s not the take of Prof. Richard Levy, who teaches constitutional law at the University of Kansas Law School. He reviewed Anderson’s written testimony from a legal perspective, noting that he takes no position on the bill’s merits as policy.

“The legislature is free to change county home rule or city zoning authority,” Levy said. “The arguments… really misunderstand the authority of cities and counties, which is always going to be subordinate to the authority of the state. I don’t mean to be saying that there are no constitutional issued raised, just that the issues concerning home rule authority or zoning power of cities and counties are policy issues, not constitutional issues.”

He was skeptical too about the claim that the bill would trample due process protections. The bill is an example of the state trying to balance one group’s rights with those of another.

“Since the early 20th century it’s been pretty much established that it doesn’t violate due process for the state to make judgment calls about competing uses of property,” he said.

What about taking away the freedom to make contracts?

“That is an argument that has not prevailed since 1936,” Levy observed. “It would be a breakthrough to win that argument.”

And it being too vague? Good luck with that — nothing is truly black and white.

“It is really, really, really easy to make a vagueness argument, and they are made all the time,” Levy said. “It’s almost impossible to write a law that has no gray areas. The bar for winning a vagueness argument is very high.”

One aspect of the bill that elicited considerable comment was the requirement that the red warning lights on towers be turned on only when planes are nearby. So-called Aircraft Detection Lighting Systems (ADLS) have been approved by the Federal Aviation Administration for several years, but the technology is not widely used.

The bill, as introduced, would have required that towers built after the law goes into effect would have to use ADLS technology.

Several opponents of the bill argued that this was attempting to usurp the authority of the FAA.

Indeed, when asked about the FAA’s position, a spokesman said that the FAA allows the lighting in some, but not all, circumstances.

Mandates for the lighting are spreading. North Dakota has passed legislation requiring ADLS technology; a bill requiring ADLS on wind towers passed both houses of the South Dakota legislature in early March without a single dissenting vote, and in Minnesota a bill is being considered that requires ADLS on not only new towers, but on existing towers also.

Following the testimony, several amendments were offered to address the concerns raised. One amendment reduced setbacks from 1.5 miles to just over a half-mile. Another exempted all counties with zoning – the setbacks would apply only in counties without zoning. Another modified the language on the lighting to acknowledge that the FAA’s decisions are final with regard to lighting.

Two votes were taken to get the bill out of committee and onto the House floor. Both failed.

***

March 27, 2019

Seiwert says HB 2273 “is not my bill…”

By Duane Schrag

Special to the Rural Messenger

TOPEKA – As he stood to address his House committee, Rep. Joe Seiwert struggled to maintain his composure. He had a written statement but faltered as he read, his hands shaking as he added the document to the testimony for House Bill 2273.

“This is for the record,” said the chairman of the House Energy, Utilities and Telecommunications committee. It was a phrase Seiwert used four times in the course of making his brief announcement. Someone – he didn’t name names – had sent emails to committee members suggesting Seiwert orchestrated the bill for personal reasons.

“This bill was not drafted at my request and it was not introduced to affect my property or gain any sort of advantage,” the statement says.

Officially, the bill was introduced at the request of committee member Randy Garber, who is from Sabetha, where there was fierce opposition to a wind farm NextEra is considering in Nemaha County.

Seiwert made his statement at the end of the Statehouse hearing on Feb. 21, which was devoted to testimony against the bill. Before delivering it, he polled staff from the Revisor of Statutes and Legislative Research offices, asking them whether he had a hand in drafting the bill.

They all said no.

“It is not my bill and never has been my bill,” Seiwert said. “I had no input whatsoever with any of the drafters of the bill. I referred them to the Revisor’s office. I had calls back home to people in my district that said that I was the drafter of this bill. That is false. I want that on the record.”

An assistant in Seiwert’s office declined to provide the emails.

“I have been the chair eight years.,” Seiwert told the committee. “I’ve been in office 11. There were some emails sent out by lobby groups and I report here for the record. And I have copies of the emails that were sent by a college professor to everybody on this committee. I have the copies and everything, so there’s no question that my involvement was charged, that I was the main drafter of this bill.

“For the record, one of my favorite phrases in the Legislature is, ‘Your word is all you really have here.’ We serve in an arena where trust and integrity are the things that allow us to work together to get things done. I take that very seriously. That’s why I am talking here. I allowed H B 2273 to have a hearing to be worked, because I believe part of our job is to consider ideas, even ones we might disagree about.”

In a later interview, Seiwert said he has taken steps to report the incident.

“I filed a complaint about the lobbying tactics of the lobbyist who gave misleading information to the county and to the chamber of commerce,” he said. “Technically could result in them losing their lobbying license.”

At the hearing, Seiwert apologized for becoming emotional.

“I’m sorry, it makes me a little nervous,” he said, “because when it hits my home front on this, [with] people calling me and saying I crafted this bill, I am not happy.”

***

April 3, 2019

Wind farms: health issues, ‘gag orders,’ property values?

By Duane Schrag

Special to The Rural Messenger

Wind turbines may be the Rorschach test for the 21st century.

To some people, those lazily spinning blades depict a future of harmony with nature and the promise of sustainable prosperity.

Others see blades that savage birds and bats, pollute the viewscape, churn out sounds and energy fields that deprive people of sleep, cause headaches and even induce seizures, and drive down the value of real estate for miles around.

Some people point to scientific studies that conclude wind farms might cause nuisances but not genuine health problems, and none of the market studies they cite can find convincing evidence of wind farms reducing the market value of nearby property.

Others say the scope of the harm caused by wind farms is concealed by gag orders that prevent landowners who lease their property from revealing the truth about what is happening.

Wind developers say they don’t impose gag orders – just ask the landowners.

Of course landowners won’t talk about them – they have agreed not to, say the others.

Opponents of the proposed Pretty Prairie Wind Farm insist they are not against developing wind energy.

“We are at a point in our country where we need to look at our options for energy, and for renewable energy,” said Kristy Horsch, a mother of four girls who lives in the footprint of the proposed wind farm. “But we need to do that responsibly.”

Horsch testified at a Statehouse hearing in February before the House committee on Energy, Utilities and Telecommunications, which was considering a bill (HB 2273) that would have prevented wind turbines from being less than a mile and a half from any residence.

Health concerns

Horsch told the committee that she has done extensive research on the potential harm of living near wind turbines, and that she believes “we need to make decisions from a place of well-rounded, exhaustive knowledge and preparation.”

“I can say that my children will not be guinea pigs in this experiment,” she told the committee. “My husband and I are entrusted with their health and safety, and … we cannot stay in an area that has the potential for causing harm under this guise.”

But there has been strikingly little success in explaining how wind turbines can cause the harms that opponents fear.

A paper published in November 2014 in Frontiers in Public Health offers an explanation, making the case for what is called the “nocebo expectations hypothesis.” The nocebo effect is related to its better- known sibling, the placebo effect.

Or, if you expect to get sick, you just might.

Here’s how the paper explained the nocebo effect: “Research consistently indicates that the expectation of adverse health effects can itself produce negative health outcomes,” it said. “Negative expectations generating nocebo responses have been shown to have a powerful influence on health outcomes in clinical populations and reported symptom experiences in community samples.”

The paper lists symptoms frequently associated with living near wind farms: sleep disturbance, headache, earache, tinnitus, nausea, dizziness, heart palpitations, vibrations within the body, aching joints, blurred vision, upset stomach, and short-term memory problems.

Becoming familiar with the list can have an effect.

“Simply reading about symptoms of an illness can prompt self-detection of disease-specific symptoms, a phenomenon seen in medical student disease,” the paper noted. It has been noted that medical students learning about an illness start to experience symptoms of the disease.

Property values

Several said property value studies conclude that wind farms can reduce residential home values by as much as 40 percent.

Kimberly Gencur Svaty, a wind industry lobbyist, testified that she had been given a study of property values in all 21 Kansas counties with wind farms.

“There was no market evidence to support a negative impact upon residential property values as a result of development of or proximity to a wind farm, and there was no reduction in assessed value,” Svaty said. “I can get you that data.”

The study by Marous and Associates is available at neoshoridgewind.com/property_value_report.

Marous and Associates focused on the Neosho Ridge Wind Farm and seems similar to studies it has done for wind farm developers across the country.

The consultant contacted county appraisers, but the study offers no record of exactly what they were asked, or their responses. Appraisers contacted for this story said there were no property sales to evaluate, largely because the wind farm footprint contained so few homes.

Opponents of the proposed Pretty Prairie Wind Farm note that the Reno County project area is significantly more populated that other wind farms in Kansas. A review of 2010 Census data shows that there are about three times as many people per turbine in the project as there are in Kingman, Pratt and Marion county wind farms.

Some appraisers said they are certain proximity to wind farms would make homes less marketable.

The study also attempts to show that wind farms don’t impair property values by comparing sales information on four homes (on in Coffey, Harper, Pratt and Ford counties) that were close to wind farms, and comparing each to the sale of a similar home that was not close to a wind farm.

This use of so-called matched pairs is dismissed by skeptics as an opportunity to cherry-pick data to support one side or the other. Here is how federal judge Frank Easterbrook put it in an opinion that addressed the value of property that lay in the path of a pipeline:

“What puzzles us is why both sides were fixated on pairwise comparisons—that is, matching each subject parcel with a supposedly ‘comparable’ parcel … and then comparing the appraised value of the ‘matched’ parcel with the appraised values of the subject parcel with a pipeline easement. That process is full of problems. No other parcel will be identical to the subject parcel except for its lack of a transmission-corridor easement. Location and other attributes always differ, setting the stage for debate about whether an appropriate comparison has been selected.”

On the other hand, supporters of the bill did not include in their testimony details of studies they say show a decline in property values.

A majority of evidence in scientific journals appears to show that wind farms do not have a negative impact on property values.

A study published in July 2014 in the journal Energy Economics examined the impacts of wind turbines in urban areas of Rhode Island. It analyzed 48,500 transactions, with 3,250 involving homes within one mile of a turbine.

“The results suggest that wind turbines have no statistically significant negative impacts on house prices, in either the post public announcement phase or post construction phase,” the study concluded.

Closer to Kansas, a study published last year in the International Journal of Housing Markets and Analysis looked at 23,000 residential real estate records in five Oklahoma counties with wind farms.

“While there may be isolated instances of lower property values for homes near wind turbines, results show no significant decreases in property values over homes near wind farms in the study area,” the study found.

A paper published in August 2012 in the journal Land Economics found otherwise. It looked at 11,300 property transactions over nine years in northern New York state, and concluded that “nearby wind facilities significantly reduce property values in two of the three counties studied. These results indicate that existing compensation to local homeowners/communities may not be sufficient to prevent a loss of property values.”

Gag orders

Confidentiality agreements are not uncommon, particularly when a developer is negotiating with many individuals for use or acquisition of their land. The developer wants to get the best deal possible from each individual.

How are landowners paid for turbines on their property? It depends.

There are estimates. Spencer Jenkins, a developer for NextEra Energy, told a House committee in February that NextEra’s Pratt County wind farm will pay landowners $1.5 million each year. For 109 turbines, that is $14,000 per turbine.

However, wind farm opponents say some of these agreements go beyond standard confidentiality clauses. They allege the agreements impose “gag orders” that can stifle information about health problems arising from proximity to wind farms.

NextEra initially said it does nothing of the sort.

“I want to reiterate that nothing prohibits landowners from discussing our projects, which many landowners do freely at public meetings,” wrote Conlan Kennedy, a NextEra spokesman, in an email. In a telephone interview he said, “We do not restrict them from speaking out.”

A lobbyist for wind energy claimed to have never heard of gag orders. The American Wind Energy Association didn’t respond when asked for a comment on the prevalence of such clauses.

But here’s what was shared with people who attended an informational meeting in February organized by opponents of the proposed Reno County wind farm. The wording purportedly came from a contract between NextEra and a landowner in Pratt County.

“The Parties agree not to make any statements, written or verbal, … that defame, disparage or in any way criticize the personal or business reputation, practices, or conduct of the other party, its employees, directors and officers.” It goes on to provide an allowable response.

“[Either party], if approached, has the right to state ‘we had an issue and that the issue has been resolved to our satisfaction.’”

When shown this particular language, NextEra said it does not appear in wind lease agreements, but “language is used in ‘participation agreements’ signed by neighbors.

“A participation agreement is voluntary and offered to certain landowners in close proximity to the Pretty Prairie wind project,” wrote Conlan Kennedy, a NextEra spokesman, in an email. “The landowner is offered a participation agreement even though they do not host any actual wind farm infrastructure on their property. The landowner receives an annual payment as consideration for being a ‘participant’ in the project. As with any contract there are certain terms both sides agree to abide by.”

The gag order is one of them. Participation agreements pay around $1,000 a year.

Participating takes the form of granting NextEra what is termed an “effects easement.” The document enumerates a variety of phenomena that might be associated with your neighbor’s wind turbines – “audio, visual, view, light, flicker, noise, shadow, vibration, air turbulence, wake, electromagnetic, electrical and radio frequency interference, and other effects attributable to the wind farm …”

By granting NextEra an easement for those effects, neighbors forfeit any right they might have had to be compensated if they experience any of them, said Stan Juhnke, an attorney in Hutchinson.

Over the years, Juhnke has seen many wind lease contracts, and they have always been restrictive, he said.

“I basically told my clients, “You are, in effect, selling the property. It’s a long-term lease; you’re giving up your right to use it as you see fit.” he said.

With the “effects easement” the adjacent landowner gives up something new.

“You are giving up your rights to sue for damages that may be caused by those things,” he said.

***

April 3, 2019

Energy, community and climate change

By Duane Schrag

Special to the Rural Messenger

Some people think wind turbines are lovely. They possess purity of function, simple geometric shapes that signal, with each slow rotation, the vast invisible energy all around us.

Not everyone shares this appreciation. To some, the great fans are a blight on the landscape; they are noisy, a source of incessant movement. Some even suspect they radiate harmful energy.

Intense opposition to the proposed Pretty Prairie Wind Farm in southeast Reno County is unsurprising. It has given rise to hostility and suspicion. Some of this is understandable, some is deserved.

At the core of the controversy is an inconvenient truth: our appetite for energy is boundless. Energy is opportunity and when it is available, it is consumed quickly. All organisms, whether plant or animal, neglecting opportunity quickly became extinct.

Until humans discovered highly dense energy ‒ first coal, then oil ‒ they didn’t gain much traction. Current estimates are that 2,000 years ago – about 10,000 years after agriculture was invented – Earth’s human population was around 300 million. By the Middle Ages it was roughly 750 million. Coal emerged as the chief energy source in the 1700s, and the first commercial oil well in the United States was drilled in 1879.

By 1900, Earth’s population was 1.7 billion. It has now passed 7.5 billion. The discovery of incredibly cheap, dense energy made this possible. Producing this energy, much of it in the past century, suddenly released carbon that had been removed from the atmosphere over millions of years. It was humans’ bad luck that atmospheric carbon affects the rate at which Earth’s heat dissipates into space.

And so here we are: addicted to staggering quantities of energy, with carbon emissions from energy use that keep climbing (by more than 10 percent since 2010) and atmospheric carbon levels that are 30 percent higher than ever seen in the past one million years.

Hence wind farms.

They are making a difference. As this is being written, strong winds are blowing in the central United States, and half the power put onto the central grid comes from wind farms (see graphic). It is estimated that last year, wind farms for the first time generated more energy in Kansas than coal-fired power plants.

Some critics argue that the push for renewable energy in the United States is futile because carbon emissions from other nations are growing. China’s carbon emissions passed those of the United States in 2006 and now are double.

But it’s also true that per capita carbon emissions in China are less than half those in the U.S. And because carbon remains in the atmosphere for centuries, aggregate emissions matter ‒ so far the United States has pumped twice as much carbon into the atmosphere as China.

This is not the time to abandon efforts to wean ourselves from fossil-based energy. Instead, it’s a good time to examine how we get it done.

Contrary to popular belief, studies show that wind has become the cheapest source of energy. Even without subsidies, it is cheaper than a fully depreciated coal-fired plant. This analysis does not factor in the societal cost of pumping more carbon into the atmosphere.

But at the same time, the total costs of implementing wind must also be counted.

The old question, whether a tree falling in the wood makes a sound if no one hears it, now has a cousin: Are wind turbines a blight on the landscape if nobody sees them?

Probably not. The corollary is, they are a blight to some citizens in populated areas. Compensation goes only to the owners of the land on which the turbines are built. That’s not fair to everyone else who happens upon them.

If wind developers were required to compensate communities, based on the density of surrounding population, development would be steered toward less populated areas.

Some might find functioning wind farms pleasing, but surely everyone agrees abandoned turbines are a ghastly sight. The logistics and cost of removing these behemoths ‒ some in Kansas are nearly as tall as the St. Louis Arch ‒ are challenging. Wind developers promise to remove them when they are no longer used, but promises are worthless if a developer is insolvent. How can we be certain there will be money to remove lifeless turbines in 30 or 50 years?

Here’s how ‒ require the developer to put money into an escrow. The state should have the authority to enforce that.

Another hurdle is the odious strategy by wind developers to rely on confidentiality clauses, even gag orders. Counties entertaining wind farm proposals should demand that all contract language be revealed during the application process. The public interest is never served by secrecy.

Wind farms can be ‒ ought to be ‒ in the public interest.

***

April 10, 2019

Wind Farm plan bumps wildlife boundary, rural population density

Hearing continues Tuesday

By Duane Schrag

Special to the Rural Messenger

Of the 88 turbines planned for the Pretty Prairie Wind Farm in Reno County, nearly a fourth of them are within three miles of the Cheney Reservoir protected area – despite state guidelines that recommend no turbines be built in that zone.

Information about placement of turbines in the wildlife buffer zone emerged Thursday during the first phase of a public hearing prompted by an application from Florida-based NextEra Energy to build a 220 megawatt wind farm in southeast Reno County. The hearing, at the Atrium Hotel and Convention Center in Hutchinson, lasted nearly eight hours.

The Reno Planning Commission will resume the hearing at 4:30 p.m. Tuesday at the hotel, 1400 N. Lorraine.

During the developer’s presentation on Thursday, NextEra representatives said they worked closely with state officials to address problems the wind farm may pose to wildlife. Spencer Jenkins, the lead spokesman for NextEra, said the company was surprised by a letter dated April 2, from the Kansas Department of Wildlife, Parks and Tourism, that raised several concerns about the project.

The letter said that nine turbines are to be built within the three-mile buffer zone.

However, a KDWPT map of the Cheney wildlife area shows 20 of the turbines are within three miles of the KDWPT-managed area around Cheney Reservoir. Some are less than two miles from the boundary.

A planning commissioner asked why the turbines are being placed within the buffer in spite of KDWPT recommendations.

“The buffer is recommended. It is not a rule or regulation. It is purely a recommendation,” Jenkins said. “The Kansas Department of Wildlife Parks and Tourism was aware well in advance of where our turbine locations were, and I can say we would not have placed those turbine locations there if anything had come up in previous conversations that would indicate that that two-mile buffer we have put in was not adequate.”

In Kingman County, a NextEra wind farm is located south of the Byron Walker Wildlife Area; the closest turbine is three miles from the protected area.

Migration corridor

Also in the letter, KDWPT noted that in a letter last year it had recommended a habitat assessment using methodology created by the Watershed Institute to determine areas with a higher potential to attract cranes. KDWPT pointed out the project site is within the migratory corridor for the federally- and state-listed Whooping Crane (Grus Americana) and the Aransas-Wood Buffalo Whooping Crane.

KDWPT wrote that, in a follow-up telephone call last month, it learned that the assessment still had not been done.

NextEra declined to provide any comment on the matter for this story.

“We will be addressing this issue at the hearing on Tuesday,” spokesman Conlan Kennedy said in an email.

The hearing drew several hundred people. NextEra was given an hour to explain its application, and then answer questions from the commission. County staff followed with their recommendation, which was in favor of issuing a conditional use permit.

Deciding the conditions to impose, should the permit be issued, remains a major task. Among those conditions:

– how to ensure roads and bridges are returned to their pre-project condition;

– compensation the county will seek on behalf of local governments to offset a state-mandated 10-year property tax exemption worth an estimated $56 million;

– how to structure a contract that ensures NextEra (or its successor) will take down wind turbines after they are no longer used.

Population density

Most of those who testified opposed the project. A recurring theme was that this project was unlike others in the state because the turbines will be placed in a more densely populated area.

According to block-level information from the 2010 Census, there is slightly fewer than one person for each turbine in the Kingman County wind farm. In Pratt County, there are even fewer people — one person for every two turbines in the wind farm west of Pratt, and one person for every three turbines in the wind farm east of Pratt.

In the proposed Reno County wind farm, there are more than three people for every turbine. The ratio of people to turbines in the Reno County project is more than three times higher than in Kingman County, and more than seven times higher than in Pratt County, according to the census data.

There simply are more people living closer together in southeast Reno County than in the areas where the other wind farms have been placed. The concentration of people in the footprint of the Kingman and Pratt County wind farms ranges from 1.0 to 1.7 people per square mile; in the Reno County footprint it is 5.5 people per square mile.

During NextEra’s testimony, the wind developer said there are about 3.5 households per section in the Reno County footprint, compared to 2 to 3 household per section in the Kingman and Pratt county projects.

The 2010 Census shows a much greater disparity. It shows 2.3 houses per section in the Reno County project area, 0.8 houses per section in the Kingman County project area (roughly one-third the density), and 0.6 houses per section in the Pratt County project area (roughly one-fourth the density).

Construction timetable

Several questions were asked about the timetable for building the wind farm. A federal Production Tax Credit, now worth about $14.25 per megawatt hour, is available for 10 years but only if construction begins before 2020. For this project, the tax credit could be worth $12.4 million per year.

Jenkins told the commission that NextEra aims to have the wind farm completed and generating power before the end of 2019, and needs to start construction by July to meet that deadline.

“We do what is necessary to meet our deadlines,” he said.

Environmental concerns

Commissioners pressed NextEra about the reporting of data on the number of birds and bats killed by turbines, specifically what access the public might have to that information. Company representatives described the internal process for logging that information, but were not aware of any way the public might see it. They did say they report deaths of threatened or endangered species to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

NextEra monitors the progress of migrating whooping cranes, and will turn off turbines when they approach a wind farm.

Included in NextEra’s application for a permit to build the wind farm was a study of sound levels from the turbines that nearby residents should expect. The study modeled sound levels at 475 locations, about half of them within 2000 ft. of the turbines.

The study reported annual average sound levels; it did not provide data on peak levels. The annual average level at homes within 2000 ft. of turbines ranged from 27 dBA to 44 dBA.

On the dBA scale, each increment of 3 dB is a doubling of sound intensity. However, for most humans it takes an interval of 10 dB to appear twice as loud.

The Centers for Disease Control lists normal breathing as 10 dB, a soft whisper as 30 dB, a refrigerator hum as 40 dB, and an air conditioner as 60 dB.

* * *

April 17, 2019

Commission planning hearing continues

By Duane Schrag

Special to the Rural Messenger

The long evolution of a 34,000-acre wind farm proposed for southeast Reno County enters its next phase on Tuesday, April 16, when the county is to announce when the marathon hearing on the controversial plan resumes.

At issue is an application by NextEra Energy for a permit to build more than 80 giant wind turbines south of Haven and east of Cheney Reservoir.

The location and date for the planning commission hearing – the date is expected to be April 22, 23 or 29 – is to be posted on the County’s web site on April 16. The proceedings will follow public comment hearings that began in Hutchinson on April 4 and were twice continued.

The next phase is to hear rebuttal testimony from County staff. The planning commission is then to weigh more than 20 hours of testimony and thousands of pages of documents as the basis for recommending NextEra’s request be approved or denied by the Reno County Commission.

If the decision is to issue a permit, the planning commission may also recommend various conditions be attached. They might include details for a road maintenance agreement, payments to reimburse local governments to compensate for a $56 million property tax exemption granted under state law, the terms necessary to ensure that NextEra (or its successor) will remove turbines when they are no longer used, an undertaking that will cost upwards of $10 million, increasing the minimum distance between turbines and nearby houses, or mandating that no turbines be placed in wildlife buffer zones.

Over three days of hearings, the planning commission twice reconvened the proceedings to hear testimony from scores of citizens, most of them bitterly opposed to the NextEra plan for a 220 megawatt wind farm.

The Messenger has reported extensively on this issue in a series of articles that began last month.

If the planning commission recommends the permit be issued, opponents will have 14 days to gather the signatures for a protest petition. If the petition is sufficient, a decision by the county commission to issue the permit must be unanimous.

Determining whether the petition is sufficient is not straightforward. For starters, only landowners in zoned areas with property within 1,000 feet of a parcel that hosts a turbine may sign, said Mark Vonachen, county planner. These are the landowners who were notified by the county of the proposed wind farm. (NextEra notified people in unzoned areas, but they are not eligible to sign a protest petition.)

If all the owners of 20 percent (by area) of the surrounding property sign the protest petition, it will trigger the requirement for a unanimous decision, Vonachen said.

He emphasized that only the portion of an adjacent parcel that is within 1,000 feet of a participating parcel counts. For example, if Landowner A owns the northeast quarter of a section and agrees to have a turbine placed on their land, and Landowner B owns the other three quarters in the section, the only portion of Landowner B’s property that is considered adjacent is the portion within 1,000 feet of the northeast quarter.

That is, 144 acres of Landowner B’s 480 acres would count as adjacent property. If adjacent property is held in multiple names, all the owners must sign the petition for the property to be counted.

It’s not yet known just how many wind turbines will be installed if the permit is issued, or exactly where they will be placed. In the NextEra application filed in February, the company said the wind farm would include 81 turbines; it listed four alternate sites. Around the same time, it filed a request with the Federal Aviation Administration for a review of 88 turbines and three alternate sites.

Over the past two months, some turbines have been moved, others removed from these plans. The Kansas Department of Wildlife, Parks and Tourism notified NextEra in a letter April 2 that nine of the turbines are within a three-mile buffer zone around Cheney Reservoir. However, a map of the locations submitted to the FAA shows 20 turbines within the buffer zone.

During NextEra’s rebuttal testimony Thursday night (April 11), a representative read a letter from KDWPT that further discussion will explore “flexibility in changing the siting of some of the turbines within the 3-mile buffer.”

NextEra declined a request to comment.

During the third and final phase of the public hearing, NextEra was given an hour and a half to rebut testimony opposing its application, and then spent nearly three hours fielding questions from the planning commission.

NextEra said it has agreed to place turbines no closer than 2,000 feet from the homes of non-participating residents, which is twice as far as county zoning regulations require. And although much of the wind farm footprint is not zoned, NextEra said it would abide by zoning rules even in unzoned areas.

“The wind developer’s self-imposed minimum setback is 1,400 feet,” spokesmen said.

However, a steady stream of opponents argued that 2,000 feet is too close. They asked for 2,500 to 8,000 foot setbacks, citing noise from the turbines and the obstruction of view.

NextEra maintains that with turbines no closer than 2,000 feet from homes, the sound level is acceptable. It submitted a study that calculated the sound level at 475 homes in and around the wind farm footprint.

But sound values in the study were expressed as an annual average, providing no insight into the maximum levels, and in particular how loud they would be at night.

Turbine noise is mitigated primarily by moving them further from homes. When asked by a planning commissioner if 2,500 foot setbacks might be considered, NextEra project manager Spencer Jenkins said it would have a tremendous effect on the project and that the 2,000 foot distance is the most possible.

Adrian Harrel, who manages NextEra’s Pratt and Kingman county wind farms, explained to planning commissioners that NextEra can and will shut down turbines at a moment’s notice if necessary — if whooping cranes are spotted heading for the turbines, for example, or for aerial spraying on a field in the footprint.

“I can shut it down with my iPhone from here,” Harrel said. “I could shut down the entire Pratt site.”

“In some cases, NextEra enters agreements with the National Weather Service to shut down wind farms during severe weather if turbines interfere with the weather service radar,” said Sam Massey, a NextEra project director.

Earlier in the hearing process, a NextEra representative told the planning commission that the wind turbines have no effect on weather radar, an assertion that was challenged by opponents.

An online screening tool maintained by the Federal Aviation Administration indicates that the proposed Reno County wind farm is in a location that does have the potential to interfere with the Wichita weather radar, and one that should be reviewed by the National Weather Service.

NextEra told commissioners it will provide NWS information about the site this summer.

The issue of interference with GPS signals, which are crucial to precision farming operations, was pressed by planning commissioner Russ Goertzen. He said that in his experience structures far less imposing than 500-foot tall wind turbines can cause interference.

Harrel and Mark Trubauer, another NextEra manager, said they have yet to receive a complaint about GPS interference from wind turbines.

* * *

May 22, 2019

Questions raised over petition

By Duane Schrag

Special to the Rural Messenger

Legal questions about a petition protesting the proposed Pretty Prairie Wind Farm have postponed a special meeting of the Reno County commission for three weeks.

If the petition is sufficient, county commissioners would have to be unanimous in their decision to issue the conditional use permit required for the wind farm. A spokesman for Reno County Citizens for Quality of Life, the group that gathered signatures for the petition, said the group’s attorney is aware of the legal question that has been raised, but declined to elaborate on what it is.

“Reno County reached out to our lawyer and he has been working with the county on this,” said Angela Mans, a volunteer with the citizen group. “At this point, he is not concerned at all. He is confident with what we have done. We worked very hard to find the exact right wording. NextEra raised this issue.”

NextEra Energy, the project developer that owns Florida Power and Light, did not respond to a request for comment.

Reno County commissioners were to meet May 21. They are now expected to address the issue June 11.

To be sufficient, a petition must be signed by the owners of 20 percent of the land that is within 1,000 feet of a parcel under lease by the wind developer.

“We have a solid 50 percent that we feel really good about,” Mans said. The group submitted signatures for 237 parcels. Half of those meet the 1,000-foot requirement and own at least half the eligible property, more than twice the required amount. The other half simply live in the footprint of the wind farm, she said.

The proposed wind farm in southeast Reno County would consist of about 85 turbines with a total nameplate capacity of 220 megawatts. Opposition to the project has been fierce. Three days of testimony before the Reno County Planning Commission was dominated by more than 100 citizens who raised concerns about the project.

Many complained that allowing turbines within 2,000 of neighboring homes was insufficient distance. The setback is twice the distance required by county zoning regulations, but one agreed to by NextEra. The wind developer also volunteered to honor those setbacks for the turbines — more than 30 — that will be placed in non-zoned areas.

The land where NextEra wants to put the wind farm is a mix of unzoned and zoned for agricultural use. In order to put wind turbines on agricultural land, the county’s zoning code requires a conditional use permit.

State law provides a process for protesting changes to zoned parcels. The statute, KSA 12-757, describes who can sign a petition, and how sufficiency is determined. Mans said the group relied on its lawyer to make sure the petition conformed to state law.

“It was under his direction how we did the protest petition,” she said.

Questions have been raised in the past about how a petition is to be presented. When gathering signatures to get a question put onto a ballot, state law requires that the person collecting signatures sign an oath that they witnessed the signatures being written, and that statement must be notarized.

In 2003, Rep. Paul Davis asked the Kansas Attorney General for an opinion on whether protest petitions submitted under the state zoning laws had to be notarized as described under the state’s election laws.

Then-Attorney General Phill Kline did not think so.

“There is no requirement in K.S.A. 12-757 that signatures on a protest petition be notarized,” Kline wrote. “… It is determined that signatures on a protest petition submitted pursuant to K.S.A. 12-757, other than the circulator’s signature on the recital, do not need to be verified upon oath or affirmation before a notarial officer or otherwise notarized.”

Mans said she takes the delay in validating the petition as a sign that Reno County officials want to be sure they follow the law.

“Reno County is being very careful to take into consideration everyone’s complaints and concerns, and making sure everything is correct,” she said.

Amy Brown, another volunteer leader in the Reno County Citizens for Quality of Life group, said the effort brought out the best in people.

“It was amazing to watch this community come together to accomplish something,” Brown said. “It’s kind of a David and Goliath-type battle and it’s been absolutely phenomenal to watch people in this community come together. There are a lot of brilliant, dedicated, hard-working people here.”

* * *

May 29, 2019

Protest petition details emerge

By Duane Schrag

Special to the Rural Messenger

The owners of nearly one-third of the parcels in the footprint of a proposed Pretty Prairie Wind Farm have signed protest petitions objecting to the project. NextEra Energy, based in Florida, wants to build a 220 megawatt wind farm in far southeast Reno County.

The Reno County Commission is expected to meet June 13 to decide whether to issue a conditional use permit to allow the project to go forward.

County staff have not yet said whether there are enough protest petitions to require a unanimous commission vote to issue the permit.

Under state law, a protest is sufficient if the owners of at least 20 percent of the land within 1,000 feet of participating zoned parcels object. A zoned parcel is said to be participating if the owner signs a lease or contract with the developer, such as for a turbine to be placed on a parcel in the zoned part of the county.

If petitions meet the 20 percent threshold, the decision to issue a conditional use permit must be unanimous.

The group submitted protest petitions for 184 of the 607 parcels that make up the 47,000-acre wind farm footprint. Petitions by the owners of dozens of parcels outside the footprint were also submitted. Only land within 1,000 feet of zoned participating parcels will be counted.

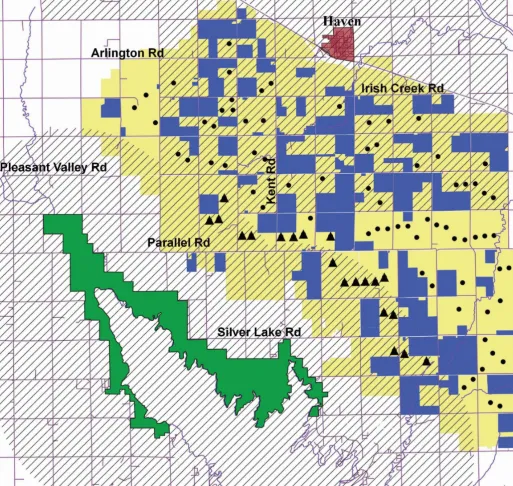

In the accompanying map, the wind farm footprint is pale yellow, the land within the footprint owned by protesters is blue, the Cheney wildlife protection area is green, and the area with diagonal lines is zoned.

About 30 percent of the footprint is unzoned; 42 percent of the proposed turbine locations – 39 of 92 – are in the unzoned area.

Proposed turbine locations are either round dots or triangles. The 20 triangles show proposed turbine locations that are within three miles of the Cheney wildlife protection area.

The Kansas Department of Wildlife, Parks and Tourism position on wind power is that “turbines not be sited within three miles of a KDWPT-managed property.” In a letter to NextEra earlier this year, KDWPT expressed concern about the placement of nine turbines within the three-mile buffer area.

Ron Kaufman, director of information services for the department, said Friday that due to a mapping error, KDWPT thought that the number of turbines within the three-mile buffer was nine, rather than 20.

In April, KDWPT sent a letter to Reno County stating that it planned to meet with NextEra to discuss “flexibility in changing the siting of some turbines within the 3-mile buffer.”

Kaufman said Friday that KDWPT has not changed its recommendation that no turbines be built in the buffer.

NextEra did not respond to an email asking whether any turbines proposed for the buffer area had been relocated or removed.

Here is a list of the owners of property within the footprint for which a protest petition was submitted:

Achilles, Kevin R & Teresa K; Adkins, Douglass S & Shawna K; Agrarian Concepts, Inc; Bartholomew, Jeff Ray & Ann; Bauman, Fam Trust & Beltz, Robert D; Bauman, Janice K & Beltz, Robert D Bauman Fam Trust; Bays, David L & Victoria F; Beltz, Janet L; Beltz, Robert D; Bender, Lawrence H; Bergkamp, Byron & Dorothy Trust; Blocker, Nellie M Rev Trust & Harold W Res Trust; BMJ Farm of Haven; Bogner, Blaine & Emily; Bogner, David J & Marsha G; Bogner, Donald L Rev Trust; Bogner, Donald L Rev Trust & David J & Duane J Rev Trust; Bogner, Donald L Rev Trust & Duane J Rev Trust; Bogner, Donald L Rev Trust & Duane J Rev Trust & David J & Marsha G; Bogner, Gerald & Michelle G; Bogner, James & Renner, Whitney; Bogner, Marcella A Rev Trust; Bogner, Matthew F Rev Trust; Bogner, Paul J Revoc Trust; Bontrager, Vernon H Trust & Arlene K Trust; Bontrager, Wendell A & E Marie; Brauer, Milton E & C Janice Rev Trust; Brown, Michael L & Vicki; Brown, Ted L & Amy M; Brungardt, Marcia K & Bogner, Andrew G Jr; Bullinger, Blake Randal & Carly; Cauble, Trudy L; Clark, Jane Ann; Clupny, Alan E & Evelyn A Liv Trust; Cokeley Trust; Coleman, Gary Trust & Sandra Trust; Cranmer Holdings LLC; Denicola, John & Debra S; Doles, Donald Wayne & Ilene; Egli, Nicholas E & Esther D; Egli, Nick; Fishburn, Phillip A & Carolyn R; Foster, Daniel & Brynn L; Giefer, Justin F & Jenna R; GLR Farm Trust; Gorges, Duane J & Wendy M; Gorges, Jennifer L & David; Hageman, Mary Lou R & Clarence W & Ewertz, Kathy; Headings Weldon & Anna J; Helmer, Charles W; Hermes, Peggy A & Johnny B; Hesket, Daniel Earl & Vallie S; Howard, Alan & Joyce; Huffman, Marvin V & Carolyn Y; Huston, Don R Trust & Huston, Jessie M Trust; JDJ Farms, Inc; Johnson, Garth Q & Sherri K; KDKS Focus, LLC; Keller, Jeffrey D & Patricia F; Krell, June Lea; Lanning, Roy D & Lois I Rev Trust; Laughlin, Nichole M; Long, Troy D; Macarthur, Buell A & Julie K; Mace, Lloyd & Georjean A; Moore, Michael K & Dorn C; Moore, Myrna F & Edgington, Glenda Ruth; Oehlert, Gary H & Cherry K; Orange Acres LLC; Otto, Paul W & Kristina M; Paney, Sylvester C Liv Trust; Paney, Sylvester C Liv Trust & Paney, Delores C; Popp, Laura; Ratzlaff, Elizabeth Mary & Austin Joe; Reichenberger, Gary L & Judy K; Rettig, Howard Wayne & Sue Ann; Roeder, John F Jr & Yvonne M; Royer, William L Trust & Leta L Trust; Scheele Farm LLC; Schlickau, Lucille B; Schmidt, Jeffrey J; Schmidt, Jeffrey J & Rachel J; Schmidt, John G Trust; Schmidt, Lloyd H Liv Trust & Rosalie M Liv Trust; Schmidt, Mark A; Schmidt, Mary L Rev Trust; Schmutz, Robert & Angel; Schoenhals, Kevin J & Nikki J Liv Trust; Scobee, Willis G & Mary E; Seiler, Neal & Stephanie; Seiwert, Ken Liv Trust & Seiwert, Betty Liv Trust; Simon, Theodore J & Sandra C; Smith, Lyn R Trust; Spencer, Wade Randall; Thalmann Land Company, LLC; Thalmann, Lynn & Stephanie Liv Trust; Thetford, Jacob & Adrienne; Tolin, Jane A Trust & Krell, June Lea Rev Trust; Tolin, Ricky L & Jane A; Tonn, Allison Rheann & Amanda Rochelle & Andrew Braden & Randall M Estate; Tonn, Lavera M Liv Trust; Tonn, Randall M; Valdois, Michael D & Denise L; Wagner, Charles G Liv Trust & Jackie Liv Trust; Walsten, Richard J & Gary D; Wary, Mary Jean Bogner & Achillies, Teresa K & Kevin R & Bogner, David J etal; Weber, Katelyn B & Rick J; Westfahl, Margaret L Trust; Westfahl, Marie Liv Trust; Weve, Robert A & Evie J; Weve, Sharon L; Whitney, Mary E; Williams, Daryl L & Patricia E; Worster, Kelsey Mears; Yutzy, James C & Linda K; Yutzy, Nathan

Caption information for graphic:

Pale yellow area is the wind farm footprint

Blue area is parcels with in the footprint for which protest petitions were filed

Green area is the wildlife protection area

Diagonal lines show the zoned area

Round dots are turbine locations outside the 3-mile Cheney buffer

Triangles are turbine locations within the 3-mile Cheney buffer

Dark brown is Haven city limits

Sources: Wind turbine locations are the ones NextEra Energy supplied to the Federal Aviation Administration in order to determine if they pose a hazard to aircraft. NextEra may have moved or removed some of the turbines since filing the locations with FAA. Parcel information, which included the parcel ID and the owner of record, was obtained from a GIS map supplied by Reno County. A copy of protest petitions was obtained from Reno County. Parcels were identified using IDs and legal descriptions in the protest petitions. Owners names were taken from those listed in the parcel map file, except when noted on the protest petition.

* * *

June 26, 2019

Money puts the bite on dissent

Opinion by Duane Schrag

Special to the Rural Messenger

There is a clarifying moment in the movie “Jaws,” when the mayor of Amity has just learned that on the eve of the resort island’s biggest tourist weekend a Great White shark has discovered swimmers are easy prey. The police chief wants to close the beaches.

“Well, I’m not going to commit economic suicide on that flimsy evidence,” Mayor Vaughn says. “We depend on the summer people for our lives, and if our beaches are closed, then we’re all finished.”

When there’s money at stake, compromises will be made, whether it is Amity Island or the southeast corner of Reno County.

The fight over the proposed Pretty Prairie Wind Farm makes quite clear that when enough money is in play, the value of everything — and in particular, quality of life — will be reconsidered.

And by rural Kansas standards, there’s quite a bit of money in play. A 220 megawatt wind farm in this part of the county can be expected to generate roughly $30 million worth of electricity each year. As the effects of climate change become more intense, you can expect the value of each kilowatt-hour to go up for years to come.

This is a very good time to own a wind farm.

The wind developer isn’t the only one seeing dollar signs. Reno County is enthusiastic about the property taxes it will collect, although the total is still only a guess because NextEra Energy, the wind developer, won’t say how much the project will cost. Assuming the price tag is $350 million and the local tax is 130 mills, over the first 30 years local governments would collect $45.5 million. If that sounds like a lot, bear in mind that in the first 10 years local governments would have collected an additional $59 million were it not for a 10-year property tax exemption granted by the state.

So it is that even though opposition was fierce and vocal, it didn’t change the minds of two of the three county commissioners.

Commissioner Ron Sellers, one of two who voted to authorize the wind farm, drove the area to see where turbines would be located.

“I looked at a house and I looked at where that wind facility would be in relationship to that house and it appeared that while a greater setback would be nicer to an individual property owner, that I had to make a decision that is best for the county as a whole,” he explained.

In the end, it’s about the money.

“While residents feel it would be a hardship, if you weigh all the economic factors involved, the potential money on taxes coming to the county, payments to landowners,” he said his decision makes sense.

Commissioner Bob Bush, who cast the other vote in favor of the wind farm, didn’t return a phone message requesting an interview. But the Kansas News Service quoted him as suggesting he is unimpressed by residents who valued their rural landscape.

“I’m sorry, but just staring at a deer in your field is not sustained economic growth,” he said.

Is the goal in life sustained economic growth? Is that the only metric guiding public policy? In the end, should it all be about money?

This controversy is rooted in some of our most deeply entrenched dilemmas. Topping the list is energy and its role in climate change. There are no serious-minded people who doubt that every new ton of carbon dioxide we add to the atmosphere is changing our climate; that’s just physics that was first understood more than 100 years ago.

Anyone who understands biodiversity and evolution knows that change has endlessly shaped the world we live in, and that the rate of change has profound effects on natural systems. The spike in atmospheric carbon over the last 150 years is unprecedented (if you look back only 20 million years). The disruptions being set in motion are legion.

The world that humans (and all other living things) evolved in is changing, and with stunning speed. We (and all other living things) are starting to face a world we are not adapted to live in.

Weaning ourselves off fossil fuels will dramatically reduce the buildup of atmospheric carbon, slowing the rate of warming, and buying time to actually bring carbon dioxide levels down to levels that dominated the past 20 million years.

Wind farms are a good start. They already provide energy more cheaply than coal-power plants, and that’s without taking into account the devastating costs associated with burning coal and releasing all that carbon into the atmosphere.

The transition to wind as an energy source in Kansas is truly remarkable. In 2018, there was nearly as much electricity generated in Kansas by wind farms as by coal-fired power plants. It seems certain that by 2020 wind will be the leading source of power generation in Kansas.

This hasn’t been without growing pains. Today there is more electricity being generated by wind farms in the central United States than the grid can reliably carry. Congestion results in wind turbines being idled. The Pretty Prairie Wind Farm, and others like it, will only add to that problem.

But a more pernicious problem is that southwest Reno County is far more densely populated than most Kansas wind farms. According to 2010 Census data, there are about three times as many people in the Reno County project footprint as there are in wind farms in Pratt, Kingman and Marion counties.

Wind farms are a great idea but not everyone wants to live around turbines. And they shouldn’t have to.

State law says that if 20 percent of the adjacent landowners don’t want the project, the county commission vote to approve has to be four-fifths in favor. Since there are only three Reno County commissioners, that translates into a requirement of a unanimous vote.

More than twice the required percentage — 46 percent — signed protest petitions. That didn’t sway two of the three commissioners.

Nor did the fact that one-fourth of the wind farm turbines will be placed within the three-mile buffer around Cheney Reservoir, in spite of the Kansas Department of Wildlife, Parks and Tourism’s position that no wind turbines be placed in the buffer.

Commissioner Sellers didn’t see any need to honor KDWPT’s recommendation.

“I’m not sure their position is all that valid,” he said. “There’s no science that birds need three miles instead of two miles to coast in and coast out.”

So for now the project is dead. It remains to be seen if NextEra Energy will now ask a court to clear the way for it to proceed. In order to succeed, it will have to find some reason why the hundreds of signatures are not adequate proof of opposition, or somehow have the dissenting vote nullified.`

Throughout the hearing process, NextEra Energy has cast itself as the good guy, committed always to doing the right thing.

Not unlike Mayor Vaughn when asked if there was a problem with going into the water.

“As you can see, it’s a beautiful day, the beaches are open, and the folks here are having a wonderful time. Amity, y’know, means ‘Friendship.'”

* * *